Interview with Martyna Turnau-Williams, a supervisor at the Regensburg Messerschmitt factory. Columbus, Ohio, USA, 1985.

Interview with Martyna Turnau-Williams, a supervisor at the Regensburg Messerschmitt factory. Columbus, Ohio, USA, 1985.

Martyna: Yes you may. My family was what were called Volksdeutsche, or Germans who lived away from Germany. My great, great grandparents settled into Poland in the late 1700s on the invitation of the Polish crown. They were given land rights and farming permissions. We had a farm that was in our family for many generations. I was born in 1919 right when the flu [Spanish Flu] was hitting Europe very badly. Because we were in the country with very little contact with others we survived. My father told me of the time the Soviet Union invaded Poland and we avoided that as well. They never made it to Masnik [a village in south-central Poland]. All was well for us until late in the 20s and early 30s. Many Germans were pulled away from the Reich and resented it; this caused the Poles to look upon Germans as not having loyalty. I was 13 when Hitler came to power in Germany. This seemed to set the Polish people against us even more, even though we did not support Hitler. In some areas of Poland the Germans were being persecuted and driven off their lands. In our area there was a land baron who was very wealthy; many called him derisively the Fat Cat Jew. He and his kin wanted to buy up all the farms to make a collective, like in the Soviet Union, my father and others opposed this. He then started trouble; in 1934 I remember the supply of feed was cut, raising prices. Local governments who were now not as friendly to Germans enacted rules making supplies going to German farms more expensive and paying less for our products. This on top of added taxes and threats from outside mobs, made my father decide to move us in 1936. He would say that we were not welcome in Poland any longer. The Reich had set up an aid office to help Germans who were forced to leave. There were many in our same shoes. I met a girl from Czechoslovakia who had about the same circumstances as I did. My mother had family close to Regensburg, and we were settled there. It was quite a shock being in Germany. I had only seen books showing photos of the great buildings. Poland did not have this same style and artistry. I will tell you also that we started hearing that the plight of Germans in Poland was not getting better. Some of the people we knew also had been forced to sell their land and leave. Often times it was lost due to the banks demanding all the money from a loan at once. There was another family that came to Regensburg in 1939 I recall; they were asked how it was. They told of their children being made fun of by Polish children, and threatened by gangs of Polish youth who would follow them home harassing them. I remember thinking as a teen girl that I would have liked to have seen that, I would fight them as I was a strong farm girl. My father was given a job at the feed and seed, and worked for the Blood and Soil [Blut und Boden] foundation. His farming background earned him a very good living in our new home. My mother was able to stay home and tend to the house. I was done with school and went to work as a counter girl for a five and dime store, it paid me just enough to have money to go out to enjoy myself. I bought a new bike and loved riding by the river for a relaxing day with friends. Then in late 1939 the war came. We knew that Hitler wanted to get back all the lands that Germany had lost after the first war. My father would say when he would hear him on the radio that he is going to get us into another war. He was surprised it didnít happen in 1938 when the Sudetenland was given back. When it was announced that German troops entered Poland, we were quite shocked. No one wanted a war, and Germany was doing so well then. I remember being fearful when it was announced that England and France declared war. I remember hearing bad stories from that first war in school. But that is my story on how I came to Regensburg.

[Above: The 'Volksdeutsche', literally 'German folk', were scattered all over the world. In Europe Volksdeutsche were found in nearly every European country. Here are Volksdeutsche from the Sudetenland.]

I know you worked at the Messerschmitt factory, can I ask how that happened?

Martyna: Yes, the war seemed to be going very well for us, Poland fell, later France was beaten. It seemed like this war would not be so bad. My father was even asked to return to our old home in Poland, the state was going to give it back, plus compensation for the losses in revenue. My father decided to refuse as he was doing very well here; he allowed the land to be sold to another German family.

He was given extra money and used that to take us all on a holiday vacation to Spain. I remember that well, it was nice and warm, and I saw beaches for the first time. Life seemed very good for us but there was still the war. When we returned on the train I saw a sign seeking workers for the aircraft plant which was not too far away.

It paid very well, and had nice modern working features. My father knew a few men who worked there and they said women were being taken to help free up men for the military. I went to apply, and after the interview I was given the job. I had to do training on airframe parts and work on a line. I think it was close to 1941 when I started.

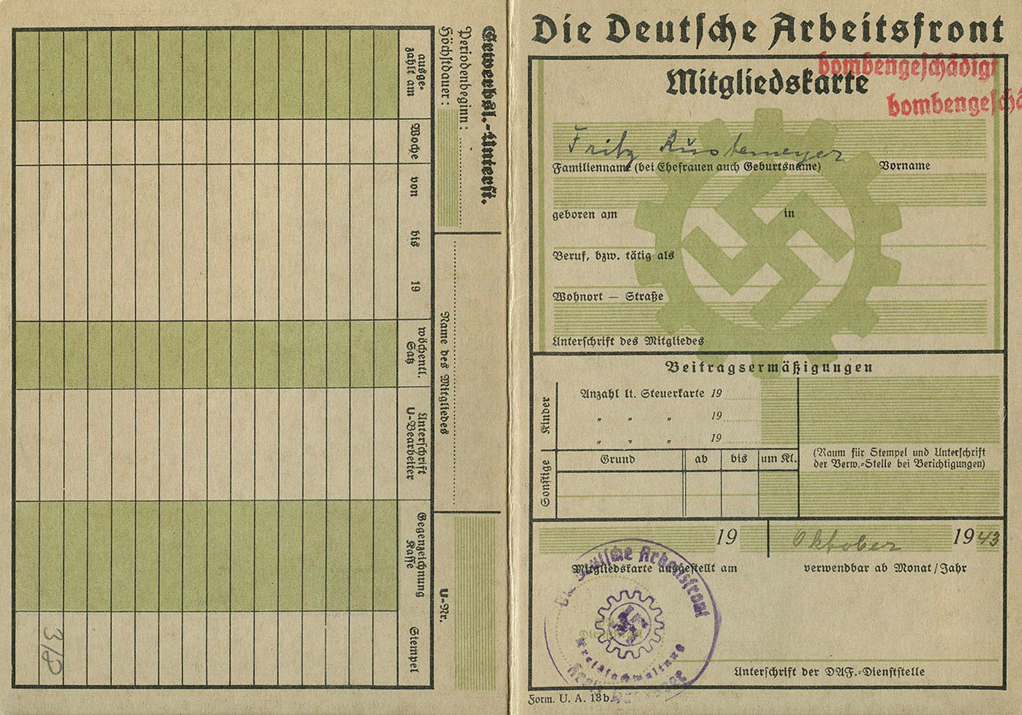

We made the famous fighter, the 109. I was assigned to the back section of the plane putting together the struts for the stabilizers and tail. The Labor Front [Deutsche Arbeitsfront, or DAF] was our union and I had to pay dues to them and taxes I remember, but the pay was good. I was always worried we could be bombed.

They had us do drills for that so we could seek shelter quickly. This plant ran all the time, I had a work schedule that gave me the weekends off which was nice, I had by now met a young man who worked in the engine sections, where he would install the engine to the mounts. We would often go out on dates with a basket to the river, or a movie.

He had to leave in 1943 after Stalingrad fell; he was taken into the Luftwaffe as a mechanic and sent to France where he was then let go and transferred to the Waffen-SS, I know he was not happy.

He was later sent to the camp at Belsen as an aide or guard and he died in 1945 from the sickness [most likely typhus, which spread rapidly throughout the camps after the Allies purposely cut the supply lines to create as much death as possible. Many thousands of Jews and non-Jews alike died of typhus and starvation-Ed.] that hit the camp before the end. It was not just the Jews who were affected; I remember many Germans died towards the end of the war from sickness.

[Above: The Messerschmitt Bf 109 was the most advanced fighter of its time.]

[Above: A dues card from the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (German Worker's Front). This was the largest organization in Germany at the time, led by the great Robert Ley.]

What were the conditions like in the factory?

Martyna: It was good for a factory I can recall. The Labor Front had a lot to do with adding good things for the workers. There was a canteen, rest area, wash rooms, and they organized many activities for us. The women with children received free child care, and we got free meals.

It was a modern complex with several buildings and I remember we had ID cards. We had to show them anytime we entered the complex, and we had to get training for spies. We all had to attend a class on how they seek information, and try to become friends to get information.

There were some buildings where they worked on secret designs, which we could not enter. We always had pot lucks and company sponsored dinners, along with movie nights and so forth. They really did a good job of keeping us entertained, to take our minds of the war.

It was a great company to work for and I really had no complaints. I was promoted to a line supervisor in 1944 due to the time I was there. We were very good at turning out the planes. It was a vast assembly line where the airframe would come in and each section had workers who put pieces on it, like a puzzle.

They would move the plane through the factory until it was finished, then it was put through inspections, and flown away. It was quite a spectacle to see something take shape from start to finish.

Oh, I remember when the bombings started to get bad, some workers had relatives who came to stay and the factory helped house them. I remember seeing a building they used, cots were brought in and they even had a soup wagon to make sure there was plenty of food. This was the Partyís doing, they took care of any displaced people.

Was the factory ever bombed?

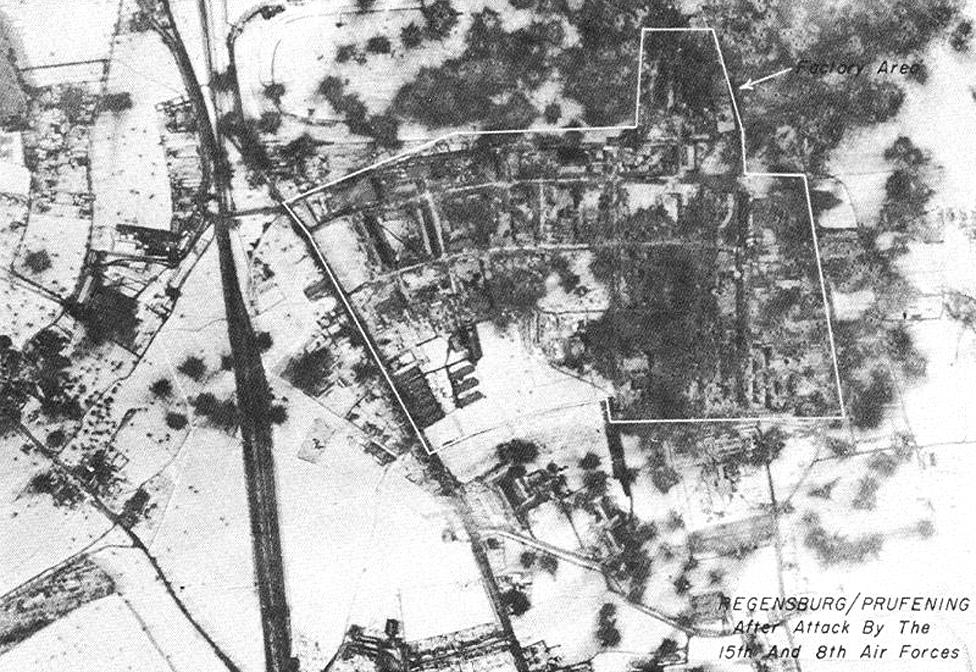

Martyna: Oh yes for sure it was. I think it was in August of 1943 when a big attack came. I was working that time and it was loud in the factory so when sirens went off it was hard to hear them. The factory had air defense people who were assigned to warn us and make sure water and hoses were ready and clear.

I happened to be on a break lying down in the quiet room so I missed when they called everyone to the shelters. I was missed in the roll call so someone was sent in to look for me. I had already woken up as I was startled by the lack of noise, and then I heard the sirens.

The man came into the room and was surprised to see me, but then said there was a raid coming. Right then you could make out that faint low drone of massed planes. The flak started shooting at them. We started running to the shelter and had just made it out of the building when the first bombs fell.

It still give me shivers, I can still feel the ground move and remember the smell. We made it inside and everyone hunkered down. The bombs fell all over the factory grounds, damaging a lot of the buildings. This lasted for perhaps 15 minutes, but we had to wait for an hour to go out.

They said the enemy would drop delayed bombs, designed to kill anyone who went out in the open after an attack. I could hear the fire service come and work on the fires. The town was not hit very badly, and many came to help us. There was an old abbey where they opened it up to house anyone displaced.

There were some workers who were in a shelter and were hit, I remember them saying some were killed, others wounded. Since I was a supervisor, I had to account for all our people, who made it though this luckily. A soldier from the Luftwaffe stopped to see the damage. He said there are many bombers who were shot down and they were getting ready to look for downed crews.

I can tell you it was not a pleasant experience to be sure. There were dud bombs that special soldiers had to come and remove. We had to go through the factory and document what all was lost or damaged. Special people came to repair equipment, and I remember seeing a lot of big wigs come too.

They brought workers with them; some were from one of the camps nearby. We worked day and night to repair the damage and I believe it was done very quickly. Shipments arrived again within a week. We were given a few days off as well so that we could rest and calm our minds.

Concerts, plays, and movies were free of charge, and food was brought in to feed us all. I was pulled into a meeting where I was told of the plans to move production into more protected areas, and to farm out production to camps and smaller factories. I was assigned to train some of the camp people in installing the tail sections of the planes.

[Above: Regensburg after being attacked by Allied bombers. Yes, Allied bombers did sometimes attack factories or strategic targets, when they weren't bombing graveyards, attacking schools and playgrounds, shooting animals, etc.]

How did the prisoners seem to be treated?

Martyna: Oh I canít really answer that as I didnít see much. From what little talking they did, they seemed to be treated fine. I saw nothing that was unusual or worrying. Many of the ones I worked with were Polish or German. I learned that in 1933 in Regensburg several Polish Jews came into the Reich illegally and were forced to leave.

There was some type of agreement that allowed them to return, in return for Polish promises of some kind. One in the group was part of this, and said he knew the city well. I heard rumors he was sent away for fencing stolen goods and having Red Front propaganda. They all worked very well, and I didnít see any problems with them.

We would have people come to talk to us often, and included them as well. These talks were to show how German production must keep up with the Allies to win the war. I remember one time where it shook me a little. The person was from the Labor Front, and they talked about how the British alone were making more planes than us.

I knew America had vast reserves and manpower, I had a fear that we would be in a bad position. The workers I had were now called unskilled as the men were called to fight. We had a mix of women, prisoners and teenagers. They made all sorts of mistakes and it slowed us down some.

I had to make sure I did training very well and watched over them to make sure things were done as they should. We kept doing better and better as the time went on, more and more planes went out since the new plans went into effect. The prisoners were included with our concerts and after hours activities for the most part.

They were allowed to eat with us and were given extra to take back to the camp at times. As I said I never saw anything bad regarding them, they worked hard and did a very good job for never having done this work before. They did get sick easy it seemed, and would get sick days off if they were bad. We did not want them coming in to get others sick, that winter of Ď44 some died I was told.

[Above: Messerschmitt Bf 109s at the Regensburg plant.]

Can I ask what your thoughts on the Holocaust are? Did you know what was happening?

Martyna: Well I certainly have my opinions and I know many here who were in the camps. The stories they tell are sometimes too odd to be believable. There is one woman who said she was at a work camp and hated it, but said there was no abuse. Others tell of absurd stories like babies being thrown into bonfires.

I can not say all the stories are false, and we knew Jews were being rounded up, that was not hidden. You must understand that Germany considered the Jews an outside people who agitated against authority. They also assassinated some officials in other lands which led to the Night of Broken Glass [Kristallnacht]. I will not try to excuse our actions, but there was a reason they happened. When the war started many Jews who were suspected of not being loyal were arrested and sent to camps. I recently learned America did this as well to Germans, Italians, and Japanese.

It is the same thing in my book, but we Germans are condemned for our actions while the other nations are excused. Our crime was that so many died in the camps but I personally believe it was due to the situation Germany was put in by 1945, many Germans were dying as well.

What happened to you at the end of the war?

Martyna: I stayed in production with the factory, moving from place to place to help train and watch over the people doing the work. The bombings became so bad that all production had to be moved to smaller areas or underground in caves. By late 1944 we were having problems getting parts as the rails were destroyed.

Work kept going until the end. Germany surrendered in May and it was all over. I stayed in Regensburg and the city became a huge displaced persons hub. I was hired on to help process all the hundreds of thousands of people who fled the Russians. We had families from Russia, Ukraine, the Baltics, the Balkans, and Poland.

I worked with American Red Cross helpers who would always tell me to move here [to the USA]. I did this work until 1949. I was put in touch with people here in the States to offer me help in finding work and a place to stay. A woman I worked with decided to move away so we made the choice to go together. I came through New York, and my beginning was not so pleasant.

When we arrived, we became separated and I was given wrong directions that took me to the black part of Harlem. I came across men who looked at me as I was from another planet. I spoke broken English and one asked me if I had money, I said no. He jumped up laughing and came up trying to grab my bag, so I took off running.

I stumbled onto a street with lots of people and I asked in German if anyone could help me. A policeman who spoke perfect German came to my aid and got me safely to the station where my friend was terrified and waiting for me. We bought the proper train tickets to Columbus and have been here ever since.

We met our husbands and settled down to raise families, leaving the war and the threat of another one behind. So that is my story, and now you maybe have a better understanding of my history.