This is a 1989 interview done in Nuremberg with Wilhelm Norkus, a veteran of 29th Panzer Regiment. Norkus fought in the Battle of Kursk and later was among the unlucky German soldiers caught in the Kurland pocket, just to name a few

[Above: The column of Pz.IV Ausf.F2, Pz.Regt.29, 12.Panzer Division, Orel, Russia, 1943]

Can I ask you about your history before the war, and what you experienced?

Willi: Sure, to start with, I was born in Zuckmantel in 1921, which had recently been turned over to the Czechs; we called this area the Sudetenland. I grew up in a poor family, where my father made a living working in a factory. I remember the Czechs made life hard for Germans; I remember the adults complained about the taxes that they had to pay and crop confiscation. This part of Germany was very hilly and wooded. I spent my younger years hiking and exploring where I could.

What exactly was the Sudetenland, and why was there a supposed crisis caused by Germany?

Willi: The Sudetenland was an area that had been part of Germany, but after WW1 it was taken away and given to the new state of Czechoslovakia. The people lost all sense of German citizenship and the Czechs pushed their form of government and customs on the people. From what I was told by my parents, this area had always been prosperous with numerous farms, and manufacturing. In 1929, it was hit very hard, and fell into depression.

The government responded by forcing former Germans to pay higher taxes, and started seizing property when payment could not be made. Many lost their homes, farms, and businesses. This caused a fierce resentment to both the Czech government and the people. The Czechs made it known they believed Germans had it too easy, and had to be punished for our former rule over them.

I was 12 when Hitler was elected, and he had huge support among everyone living in the region. Largely due to his promise to reunite the former lost lands with Germany again. I started to hear stories about people who supported Hitler being attacked, and some business owners had shops looted or windows broken. This was in the larger cities with a small German minority.

As the years went on violence started to get worse, I have heard that Czech gangs who hated Germans killed some who refused to submit. A NS movement was formed and defense units were created to help protect Germans from the violence. I know in 1937 a farmer near us was beaten badly and a band of these bandits took his harvest. The Czechs did nothing. Germany did not cause this crisis, the Czech government did by not giving Germans equal treatment, and allowing violence against us.

I remember 1938, when Germany was given back the land, people were ecstatic and had a sense that relief had come. There is even a famous German photograph that Time Life has been showing where a woman in the midst of others is giving the Hitler greeting and weeping. They caption this as a Czech woman crying due to the German invasion, but in truth, it is a German woman who lost her husband due to Czech criminals, and she is weeping because she is happy to be under German protection again.

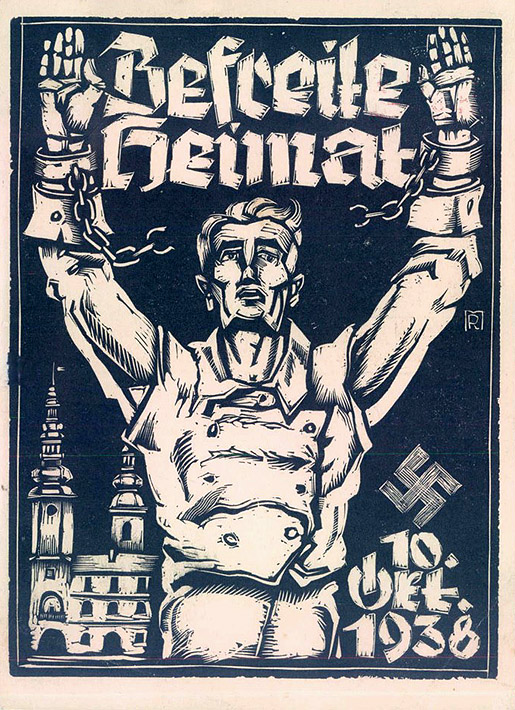

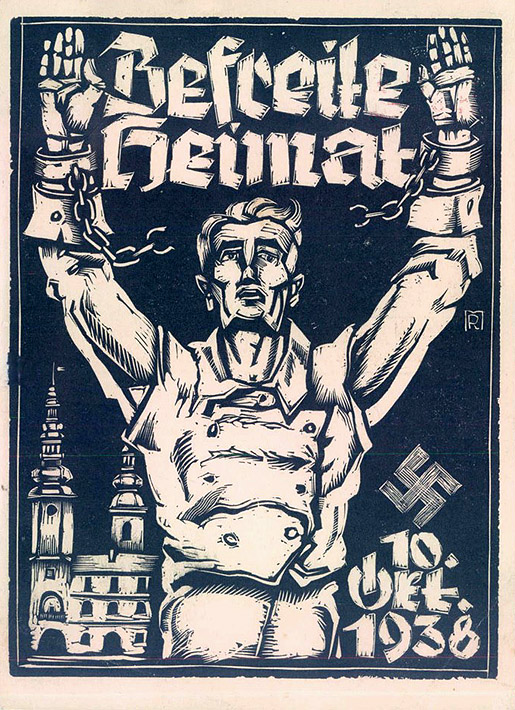

[Above: A stunning Sudetenland postcard, 'Freed homeland', sent October 10th, 1938]

What brought you to the panzer arm of the Wehrmacht?

Willi: When war broke out with Poland, then England, many of us knew our days in civilian life would be short lived. My friend was Kurt Knispel, and we both had an interest in mechanical things. Our fathers knew each other also and we were going to follow their example in building autos. We talked about what it would be like to be drafted, so we agreed we would volunteer and control where we went. I thought perhaps U-boats first, or a plane mechanic, but Kurt wanted to go to the front.

Therefore, we agreed we would go enlist and seek out the panzer arm. We accomplished this, and were promptly sent for basic training. We were sent to Sagan and it was there the adventure begun. I adapted well to military life, as I liked the outdoors. There was a lot of marching, and learning terrain navigation. The food was very good, even though it did not suit everyone, some complained but were quickly brushed off by our trainers, and the cooks made sure they got less to eat.

I liked the black wrapper of the panzer arm; it stood out and looked elite. We could go into town sometimes, and I liked showing it off to the pretty girls. I took pride in how my uniform looked, I always made sure it was to regs, but Kurt was the opposite. He was very cavalier and had no time for pomp and polish. He wanted to get at the enemy and would say, “in battle your dress doesn’t matter Willi, it’s how you fight”. That was how he lived.

[Above: Kurt Knispel, tank destroyer extraordinaire, with almost 170 tank kills. Truly amazing.]

What do you remember about Kurt?

Willi: He was quite a character. He was very simple and did not have time for the complicated. That is why he conflicted with many officers. He hated it when a new officer would come into our division without combat experience, and start preaching to everyone how to fight. This was all too common. I trained with Kurt for 1940 and into 1941; he was assigned to the third company of panzer regiment 29, of the 12th panzer division. I went to the first.

We were sent to prepare for Barbarossa [campaign against Russia], but we did not know it at the time. We practiced with panzer grenadiers, and working with breakthroughs and defense of captured ground.

It is my understanding he hated the Nazis and was like a Sgt Steiner type person from the Cross of Iron.

Willi: I do not know of this Steiner person. I can tell you Kurt was not a politician; he did not have a love for politics, but he admired the Führer. He was happy to see a politician actually do what he said he would do, when many had not. He told me Hitler was a frontline soldier, and he liked that trait, as he was one of us. I also know he did not care for the SS, at least at first. The reason being the SS was more a private NS army, and not the German army. There was a big rivalry in the beginning, and goes on today.

The SS getting weapons much needed by the other branches was a big reason, and they had not proven themselves in battle. However, I can say that as the war went on they earned our respect, and saved our asses more than once. I met Kurt back home in early '44 I believe and he spoke very highly of the toughness of the SS tankers, saying we should have volunteered if we were smarter. I never heard him speak badly about the party, or the Führer, maybe at war’s end he changed, but I doubt it.

Kurt had an astounding kill tally; I believe it was 160 confirmed, so he proved himself repeatedly. It was with great sadness I learned he fell right at war’s end. Never being found, so no one really knows what happened to him. One of his comrades, who attended a reunion, said he was attacked by a strong force of Russian tanks, knocking out what he could, but also being hit badly. He died shortly after but the enemy was coming so he had to be left on the battlefield. Someday maybe he will be found.

We parted ways in 1942, Kurt went on to Putlos for further training on new heavy panzers, I chose to stay with my company as I felt well suited, and got along with our spiess. As I mentioned, Kurt had no time for anyone telling him how to do his job, so he was encouraged to go by our CO.

What was your opinion of the Russians and the Russian soldier?

Willi: The soldiers certainly did themselves no favors by the crimes they committed, but the civilians were wonderful. We had very good relations with the civilian population wherever we went. I can tell you a funny story about Kurt. Our regiment paused in August ‘41 for a week to rest it was hot and boring. We stopped right outside a small hamlet, first thing Kurt does is go up to a police unit and asked if any pretty Russian sweeties were around, they pointed him to a small farm a km away. He took the spiess’s car and a short time later drove back with a pretty blonde girl and her sister who was not so much.

They brought milk and bread, and had dinner with us. He produced some schnapps and got them both tipsy, where he then disappeared with the pretty one. I was left staring down a comrade for the attention of the sister. However he would not budge, so we taught her to play skatt [a card game-ed.], and my comrade got her to loosen her top a whole lot so we had something nice to look at for a while.

This played out all over the east front, we were always invited to stay with babushkas and they cooked very well. The only times there were problems was if partisans were in the area, the people were terrified as they would be killed if they collaborated with us. The crimes of the partisans were particularly nasty, and had to be dealt with severely to stop them. They once used a mute to bring a grenade into our camp and put it in a panzer, but she gave it to a sentry instead. They wrote simple instructions for her that she could not follow. We sent her behind the lines to a rest home for the infirm. The northern front had a nasty habit of hiding partisans, it was hilly, swampy, and had mostly backcountry. There were small hamlets; sometimes partisans, who killed off anyone not enthusiastic to help them, or seized them. German allies usually were brought in to take them back.

You were at the battle of Kursk. What was it like?

Willi: Kursk was a hard fight; I was in a new company and had a long barrel mkIV panzer that could now knock out anything it faced. Pz rgt 29 was withdrawn from the Leningrad front and sent south to the Orel area. Soviet aircraft constantly flew overhead, and everything had to be hidden. Partisan activity increased so getting our forces built up was a slow process. We were a small force compared to the Soviets; I think we had a little over 500k men where they had 1.5million. In the speeches our leaders gave, they talked about this, and said we had to fight like a fanatical lion to erase this advantage.

When the attack began, we had orders to charge into the flank, but it was slow going, there were mines, and barriers every inch of the way. We had massed artillery hitting us, snipers, and even mine dogs. They actually trained dogs to bring mines to our panzers and rest under the soft bottom to blow it open. We were forced to shoot these animals down before they reached us.

Our panzer took some anti-tank hits but they bounced off as we stacked extra track links to offer protection. I was now a gunner, and was seeing target after target that my commander was missing. I felt like I was commanding the panzer, as I was sending the shots. We knocked out several AT fronts, and smashed through, only to be held up by mines. Sappers had to clear them. We made very slow progress, but we did make progress, kilometer-by-kilometer, forcing open the front.

We faced massed Soviet tanks; we and the other panzer rgts had a field day. We knocked out so many tanks I could not keep up. We constantly needed to be rearmed. One scary situation was a rata strafed our panzer and wounded our commander. I took command, getting us to where he could get help. I took over, and requested my friend join us as a gunner. We went back into action and knocked out three t34 tanks and several rocket trucks. We captured a whole company of these. I remember how hot and sweaty we all were. It was constant fighting.

It is often said we lost the battle and had no chance, but this is wrong. We were severely beating the Soviets and had advanced past their defenses, but due to the situation in Italy, some of our best divisions had to be withdrawn right at the height of the battle. It caused the initiative to be lost, and made us confused. If only we could have been given a few more days our panzers would have completed the encirclement and more than likely annihilated the enemy.

I say this because our LW was keeping Soviet planes away, and held air superiority when they were in the air. This gave us freedom of movement; our artillery suppressed enemy batteries after they figured out their positions. The minefields had mostly been gone through after day four, and the morale of the Soviets was breaking. We took thousands of prisoners, and we could taste victory. We were outnumbered 3 to 1 in every category, yet were overtaking the Soviets. Some kill ratios were 30 to 1 by the end of day five. Manstein agreed, even with their large reserves, we had victory at hand but some generals were not confident and swayed the Führer to call off the battle. We were stunned and angered.

What was it like after the Kursk battle?

Willi: We were sent back up north again to rest, it was quiet, as the Soviets were engaging army group south. We rebuilt and fought small battles or were rushed around to stop breakthroughs. After Kursk, our mood changed, it felt as if we had lost the eastern war. Hope was now on beating the western allies to bring a negotiated peace. We held our lines until July of '44, when the massive Soviet offensive was launched to help aid the Allied landings.

I was able to take leave early in '44 and went home on leave and to attend a panzer commander course and train on the new panther. I met a girl during the course who was a secretary on the base. We really hit it off, and she was very nice to look at. I was sent back in mid-44 just in time for the Soviets to push us back in full retreat. We ended up in what is called the Kurland pocket.

It was a very large area of land, and there were many divisions inside. We had to hold the pocket, as there were secret U-boat’s that were stationed in nearby bases. The hope they and the many new weapons coming out could change the war was great enough for us to hold this pocket. We held up despite attack after attack. We did not surrender until the end of the war. Although food was sometimes scarce, life in the pocket was not really that hard. We had access to ports, and surprisingly some units were evacuated while we also received supplies.

We did not give up until ordered to do so. We then were sent to POW camps and I ended up being lucky and avoided Siberia. The Soviets did try a lot of brain washing, and mind torture. We each had a trial and the usual sentence was 20 years hard labor. I know now that the majority of Germans and our allies taken prisoner never survived. The only ones they let go were the ones singing the praises of Stalin. Many had seen the evidence of communist crimes and knew Hitler was right in attacking Stalin, so had no desire to bow to him.

I was held down south where it was warmer, since I had a mechanical background I was used in a factory to build tractors. This was very important to them to help farmers grow crops, and did so well at this, I was made a shop leader and I played along with the party leaders. That is something you had to do to survive, and it made life easier, and brought better food. I even met a Ukrainian girl who was a prisoner, she told me of the terrible revenge brought upon them after we retreated. Her parents were killed, and the as the NKVD shot them they proclaimed the Germans did this. Their crime was providing food to us. I was held until the end of 1949, and finally allowed to return to a home that was taken over by Czechs. The Germans in this area were all expelled including my parents.

Back to Interviews