Interview with Julius A. Haber, member of 20th Panzer Division, Panzergrenadier-Regiment 59, Germany, 1999.

[Above: Brave young Panzergrenadiers, somewhere in the expanse of Russia, riding atop a Sturmgeschütz III (StuG III) assault gun.]

What attracted you to join the Wehrmacht, or were you drafted?

Julius: I was conscripted at 19 years old, right after I spent my time in the labor service clearing bomb rubble. I lived near Erfurt, which was home to many regiments of the Wehrmacht. I was sent a telegram that our postal girl delivered and she told me many men were getting these today, and she asked me to open it with her. It stated I was part of the third call up, I believe. My parents were fearful, but I was eager for a new adventure. The postal girl asked me to write to her as her brother was in the army too. I was very happy, as she was very beautiful.

In January 1941, I reported for duty. I ended up assigned to the training battalion of the 20th Panzer Division, and further assigned as a Panzergrenadier, since I had a driver's license. The first part of training was basic military, which lasted about 2 months; it was intensive physical training and made us ready for life at the front. We learned weapons handling, first aid, military law, and above all, trust in your comrades.

One rule that was stressed was we do not lock our doors or lockers, we must have trust. Our training NCO stressed that in our society, or Volksgemeinschaft [people's community], trust in each other to always do right to everyone was the most important. There was no room for thieves and liars. We were ordered to leave money and possessions unsecured. We never had any issues during all of my training with theft, and indeed, throughout the war, we always looked out for each other.

The second part was specific to Panzergrenadier and Panzer training. Our NCOs were old hares from the Polish and French campaigns, and they were very hard on us. We did enjoy their stories about the front, and what we could expect when under fire. After this training, I was sent to my final unit, Schützen-Regiment 59. No sooner had I met my commander and NCO than orders came to move to east Poland, so we took a week to board trains for the journey.

You were present during the opening of Barbarossa, what do you remember?

Julius: It started as an exciting adventure, then later on a nightmare. My new unit was sent east of Warsaw, as we passed through I marveled at how large the city was, and there was little evidence of the war. I had heard we destroyed a large part of the city, but it must have been rebuilt. We were in cattle cars, and I remember seeing many trains, all carrying military vehicles and personnel. I still see the shapes of the Panzers, which were hidden under tarps protected from spies, but anyone could see they were Panzers.

Rumors abounded that we were soon going to come to blows with Russia; they had invaded many countries in Europe, and threatened others. My good friend Dieter, who was in the Pioneers, was sent to Romania, and reported very good relations with the Roma they encountered, especially the pretty girls, but they did have to watch for thieves.

The month of June was spent training and cleaning our equipment. I was surprised that our regiment still did not have armor carriers for us as we should have. There was much grumbling about our supply chain not getting us all the equipment we needed. I became very good on the MG 34 and was awarded an machine gun marksmanship award for a competition we held. I noticed the whole time we were in our billets that planes were flying high overhead and heard many engine noises. It was easy to see something big was in the works.

On June 21, we were ordered to turn in early and all equipment was made ready for inspection, but with all weapons having extra ammo, which we thought strange for inspection. Plane motors awakened me very early, and soon after, I could hear booms in the distance. We were ordered to ready our positions and we assembled. Our officers soon told us we were at war with Russia, and that this was a preemptive attack to save Europe from Bolshevism.

We moved at once and I could see police trying to direct huge traffic jams. We took all day to get into the Soviet side of Poland. As soon as we came to the first town, the fighting was over as our recon units and Panzers drove the Russians out. The remaining town's people came out to welcome us and give us water and bread; we gave them chocolate and whatever items we could part with. Our objective was to push past Bialystok [the largest city in northeastern Poland], which we could see burning in the far distance. I started to notice the amount of Soviet equipment, it was everywhere, on the roads, in the fields, and strewn in the towns. Vast amounts of stockpiles of food and ammo were found, which indicated to us the Russians were not in defensive positions.

A regiment in front of us engaged an armor unit and knocked out or captured dozens of tanks that looked like they were being hidden, yet on parade. I saw my first prisoners who looked well dressed with nice new weapons. We stopped for a rest, and I jumped down from the lorry we were riding in. I went over to a group of Russians and tried to speak to them, but no one spoke German and I only knew French and English. I traded some bread for cigarettes, as many of us smoked to help calm our nerves.

One strange incident I remember was a police officer came over to the prisoners and started speaking very loudly so they could all hear. He was asking if anyone wanted to volunteer to help our cooks to avoid P.O.W. camps, all raised their hands and were put on trucks, or started marching with us. It was strange to see your enemy now wanting to help you. They had guards assigned so they could not escape, but it was very relaxed.

Those first weeks went fast; we marched, had contact with the enemy, rested, and marched again. I was amazed at all the men and equipment we saw. It appeared either Russia was much underestimated for her strength or she moved all her troops to our border. There were endless columns of prisoners, mountains of equipment and supplies. Capturing the supply depots was good, because we were short of food and had a hard time feeding all the prisoners. We would joke Stalin would have a tantrum if he knew his captured soldiers were also eating his captured food.

What was your impression of the Russian soldier?

Julius: We faced many types of Russian soldiers, the European and the Asiatic, conscripted to volunteer, party fanatic to anti-Bolshevist, and humane to evil. In the beginning most every Russian soldier we had encountered was not fanatical, the only ones who were ended up being the commissars. They were pure evil, following Stalin's scorched earth to the letter, and killing any Russian who resisted having their farm or town destroyed. We came upon many scenes before Minsk and beyond where the retreating enemy laid waste to everything, anything they could not take was destroyed.

We were appalled at the cruelty we witnessed while entering some areas, whole families who resisted retreating were shot down, survivors saying political officers had them shot. You have heard Hitler gave the order to execute these criminals, I saw none of this until we were well into Russia, and then the police units would take these prisoners away from the rest. A friend in the police said they were sent to special camps in the Reich for intensive interrogation instead of execution, but if proven they had committed crimes they were shot.

As the war drew on and we faced the soldiers from the east, the level of cruelty grew. We came across our own soldiers, as early as November '41, who had clearly been executed after surrendering. Our commanding officer ordered that all prisoners we take be thoroughly interrogated to see who is responsible.

I have to say, for the most part, the majority of Russian soldiers were well behaved and once captured were very friendly with us. We used many ex-prisoners as Hiwis [Hilfswillige, voluntary helpers] who stayed with the army and did small tasks like cooking, sewing, cleaning, and manual work. They had no guards and were free to roam. I learned they were all returned to Stalin and shot at war's end.

At war's end the level of cruelty the Russians showed is beyond comprehension. More is coming out today about the rapes of women and many more atrocities, they have just admitted that Katyn was a planned crime against the Poles, after Germans were accused and executed. In the coming years you will hear more about the hushed up crimes committed against the Axis nations.

[Above: Asiatic soldiers drafted by the Soviet Union after surrendering to the German forces.]

Most people who study the war would understand that it was the Germans who committed crimes against the people of Europe, leading up to genocide, do you disagree?

Julius: I am unable to agree with that. After I was captured, I was forced, along with civilians, to watch the movies of the camps and what the SS did. I did not believe it, as I lived through it and saw with my own eyes what happened. The Allies made it impossible to make a life after the war if you disagreed with them. My comrades and I went along with the shame and guilt; there was no point in challenging their claims. However, because we were silent and did not speak I feel like we missed a huge opportunity to tell our side, which our silence only made us look guilty as charged. We just wanted to get on with life and love our families, whom we missed dearly.

I do not wish to discuss the Jews, they are a separate issue, and we Germans cannot easily defend our position regarding putting them in camps and what happened later. I can address what I personally saw, and that was the conduct of the war by the German Wehrmacht. We had very strict orders to treat every civilian with compassion and respect. There was nowhere in the Wehrmacht's orders to harass or detain anyone, unless they were suspected of partisan activity or harassing military personnel. I never had to deal with this; everywhere Panzergrenadier-Regiment 59 went, we were treated well by the civilians.

In Russia, the people who stayed behind welcomed us as friends and liberators. We stopped outside of Minsk and our engineers helped rebuild a church that the Soviets had turned into a barn. The people thanked us with a huge feast including vodka and dancing. These stories that the Russians started telling at war's end, and still cling to today, make no sense. Everywhere I went the Russian population was left alone by us and welcomed us anytime. We gave them help in restoring necessities scorched earth took away. I went through Minsk in '43 and it was mostly restored and back to peacetime. It was very important to win the hearts of the Russian people so why would we be cruel to people we relied on to help us?

But there are many eyewitnesses who claim to have seen regular Wehrmacht soldiers commit crimes against the Russian people, everything from forced labor, humiliation, beatings, public execution, and rape.

Julius: The problem with many of these stories is anyone can be an eyewitness, just because they said they saw something does not make it the truth. The NKVD [The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, responsible for millions of civilian murders] coached many people, who testified at trials, that is no secret. Remember many people were Bolshevists who opposed us, so honesty was not at the top of their priorities; it was to make the Nazis look bad, and to make their cause look just. The hate was so great that they sent many innocent people to their deaths, just because they were of a different political party. I have spoken to some people who think they saw a war crime by us, but after talking to them further, there is always more than meets the eye.

For instance if we caught saboteurs we turned them over to the police, and many people would see this. If they were found guilty, they were publicly hung or shot. The Allies would have you believe everyone we grabbed was just out for a peaceful stroll with their children in hand. I must admit to you I wish our policy had not been one of public execution, this was an old tradition that sadly we did not stop. I felt sickened watching people die, even if they were guilty of terrible crimes against us. It would have been better to do what the western allies did, they executed behind closed doors during the war.

We cannot escape the image of being criminals, but I do not believe the whole Wehrmacht is deserving of that label. We fought a war we were ordered to fight, against overwhelming odds, and against very cruel enemies. Unlike in the first war, wartime propaganda did not die, it has grown and grown. Today it is believed we killed just about every Pole and Russian we met, killed prisoners of war, raped without restraint, and literally destroyed cities just for the fun of it. It is all wartime propaganda that just will not die. However none of it is true as far as I am concerned.

Can you tell me what the hardest combat operation you participated in?

Julius: It would have to be Operation Typhoon [Sep 30, 1941 – Apr 20, 1942], the drive to take Moscow. We were in constant action on the new Ost Front; no leaves were approved in my regiment except for family emergencies or bomb damage to homes. The Russians had been in a steady retreat, only making a stand in August at the Stalin Line, which we broke easily but with heavy losses. Our fight was harder and harder, the T34 was hard to knock out, as it was better than all Panzers at the time. Panzer Regiment 21 only had light tanks which were easy for the Russians to knock out. We used flanking attacks many times to trap the enemy and force a surrender, which worked well. We kept seeing more and more material and wondered how they could make so much when we had taken many of their industrial areas. U.S. and English tanks, equipment, and planes were showing up. America was supposed to be neutral but clearly favored the Allies over Germany, and violated the rules by aiding them. I saw my first English tank in Russia; it was knocked out by Heer flak guns.

By Oct '41, it was starting to get cold, and we had little in the way of winter clothing. Our baggage trains were left way behind, so frantic calls were made to get us any winter clothing, something the home front did well. It appeared the war would be over soon and we had that huge burst of fervor to finish. We were only 100 km from Moscow and the Panzers worked closely with us to achieve breakthroughs of any position. Our losses were mounting though, many friends were being wounded, and some fell.

Replacements were slow to get to us, and the Russians seemed to be getting stronger. For the first time I saw the Asiatic soldiers and they seemed defiant even when broken and captured. The weather turned against us also, the mud was the hardest part, and we did more pushing to get vehicles unstuck than I care to remember. The Russians counterattacked some divisions, who by now were all understrength, and routed them. I was freezing, wet, and hungry as food had dwindled to nothing.

The Luftwaffe had to drop supplies for some areas, and this was not enough.

Just as German forces were on the outskirts of Moscow, and victory seemed assured, a massive counterattack hit us and pushed us back many kilometers. I remember we were in a hamlet very close to the Rollbahn [a one lane road, for example, in WWII, described key routes designated by the German Wehrmacht] and heard lots of firing ahead of us, radios cracked that we needed to move up and orders came to assemble, but before we could the order to fall back was given. We thought we cannot possibly be retreating. The Russians attacked the center front, we heard battle sounds, and saw Russian fighters attacking, it was sobering.

Ivan hit the center front with a massive attack with all the divisions they moved west, since Japan made it clear they would not attack them. I saw abandoned German equipment everywhere, now it was our turn. We used anything that could move, and we also had the burden of civilians retreating with us, which slowed us down. The Russians shelled and strafed these columns, causing terrible casualties. We had to do this in bitter cold, miserable weather with no food or water. Our leaders assembled us and told us the Führer had given orders to not take one-step back, our commander agreed, as we were losing equipment that could not be towed back.

This added to our resolve, and winter clothing started to arrive, as temperatures plunged. The Panzer Regiment started to get replacements and we quickly went into action against vastly superior forces, but we stopped them. Through December and January we held defensive areas and held Ivan back, as more and more reserves came to us. During one attack in January a mass of ski troops hit our line, I can still see the face of the soldier who raised his rifle at me, faster than I could my MP 40. I was hit in my chest and fell back into darkness.

Helped by our medics, I was rushed to the field hospital and then put on a train back to Germany after being stabilized. I was in much pain but the nurses did a great job of keeping me company, which helped with the pain. I was able to spend the next few months resting and healing; my family visited me, and in May I was discharged and given 3 weeks leave. News from the fronts were good; we had weathered the Russians, and taken the fight back to them, causing heavy losses.

[Above: A Panzer IV Ausf. G of the 20th Panzer Division, winter.]

Was there any animosity in regards to Hitler? The films of today show the average German soldier was against Hitler and the Nazis and made fun of both.

Julius: I never saw any of this. The Führer was our leader and all Germans viewed him as the person who saved our nation and pulled us up again. After the war I heard people claim there were severe laws against criticizing party leadership or the Führer, I never saw this. The party did not have an iron fist on us, unlike what is shown today. You could walk down many streets and see nothing about the NSDAP or SS. The photos and videos are largely for propaganda to make it seem like the party was everywhere, but it was not. Do not confuse displaying our national flag with being a party member.

Hitler saved Germany, and he may have saved all of Europe from Bolshevism. It is my hope that one day the hatred will die, and people will be more objective. I believe we attacked Russia before Russia could move west; it seems to be common knowledge that Bolshevism had the real aim of worldwide conquest. They were very open about that, so it was only a matter of time before they moved west. Hitler had to know of this and decided to strike first, as he was told they were pretty weakened from Stalin's purges. I know today that he made many attempts to end the war, but Churchill was bent on destroying Germany. I believe Hitler fought because he had to.

Even at the end there was a feeling of sadness about what happened to the Führer's dream of a unified Germany and culture of the highest ideals. To see our cities flattened and all lost just did not makes sense, I always ask how it could have ended so badly. Of course, the answer today is that the Führer was a lunatic who wanted to conquer and kill, and used Germany as his weapon of mass murder, but I do not believe that. After the war people said bad things about our leaders, but I believe it was what is called Stockholm Syndrome today, the Allies terrified us so much during the war, that after, people were glad to make the victors happy so they would be merciful.

What happened to you at the end of the war?

Julius: I rejoined Panzergrenadier-Regiment 59 and fought at Kursk, and the retreats in 43/44 and by 1945 we were very worn out. We had hardly any Panzers to speak of, very few vehicles, and little to no food. We were done by March. We just had no more to fight with and anything we did receive was quickly put out of action due to constant air, artillery, and tank attacks. The enemy made sure we did not rest. In March, we were ordered to relieve Görlitz [a district in Saxony, and the easternmost in Germany], along the way we were attacked by fighters and I was severely wounded by bullet fragments. Again, I found myself in the hospital around Munich. I had a pretty nurse my age who cared for me and on May 8th it was announced Germany surrendered. She cried in my arms and wondered what would happen next.

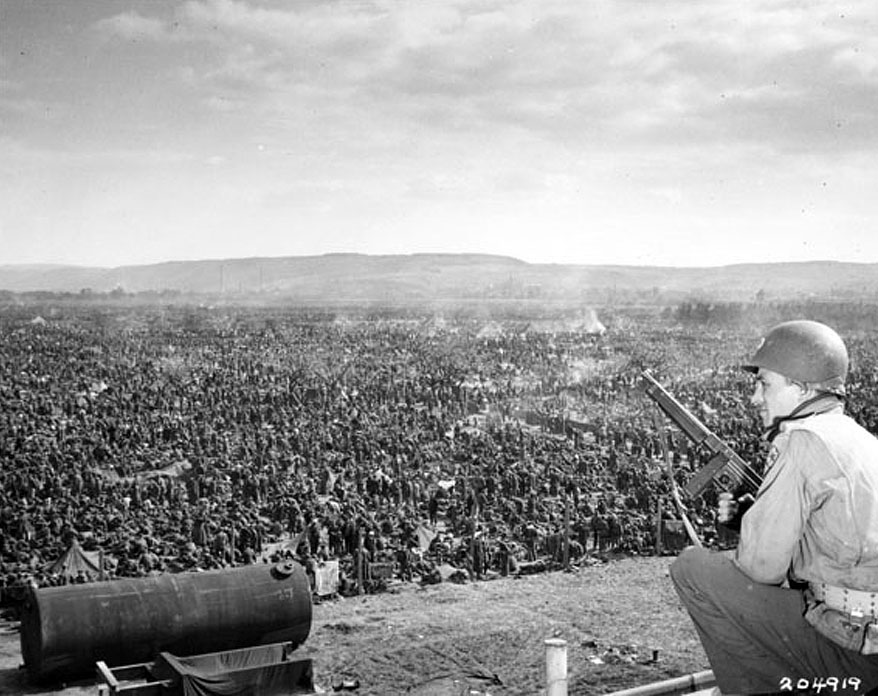

I had healed fairly well when American and French soldiers came to the hospital; I was dragged away with several other soldiers who were lightly wounded. We were told that we were going to camps to be registered and released. This was not true, I was taken to a holding area, and since I had no chance to get my Soldbuch [Soldier's identification and information book] I could not prove who I was. When I told the officer, a former German communist who now served in the French army, my unit and predicament, he labeled me as a Panzer soldier who fought the Americans. I told him I had never fought the Americans but he just brushed me off and called for the next man. I was surprised to see women and young in the camps as well. I was sent to the Rheinlager camps which were under American control, but had Poles and French as guards. They were very unkind, and deprived us of food. This was in June '45, and I had lost a lot of weight. The camp I was in was huge, it was used as a transit camp to ferry prisoners to other camps. I started hearing the horror stories about what happened to our civilians at the hands of our enemies.

These camps were massive, spread throughout the countryside, there was no sanitary facilities, hardly any food or water, and the guards were cold and cruel. We were left out in the hot weather during the day and when it rained there was no shelter. Civilians who saw our plight tried to bring what little they could spare, but the guards took the items and never gave them to us. I overheard one of the prisoners, who was a gruff old NCO, ask why they were treating us this way, and the guard replied that it was orders, and perhaps we should have thought about that before starting the war.

One night we heard gunshots and yelling, in the morning we heard a guard opened fire into the camp, killing and wounding a few. It was terrifying, I dwindled down to skin and bones, and we started getting sick. By July I noticed prisoners being carried out in the morning, these were men who died at night. I began to wonder why this was happening. By the rules of war, we surrendered and should have been paroled to return home.

It has been argued that we did the same thing to Poles, French, and others. The reason we held some of them was that their nations were still at war with us in exile, so they did not surrender, they were conquered. Germany unconditionally surrendered on all fronts, the war ended, but many did not return home for 10 years. That is a crime, yet no one speaks about it today.

I understand that through complaints from high levels, these camps slowly started to empty, by Oct '45 I was sent to a camp in France. I was truly disgusted, as I wanted to go home. I was told never to mention I fought on the Russian front, I removed the ribbon from my tunic, and my Panzer assault and wound badge was stolen by American soldiers. All I had left was my Iron Cross ribbon, of which I was still very proud. At every new camp I was interrogated, checked for the SS tattoo, and questioned about my service. I learned to say I was forced to enlist, that gained sympathy, and that I hated the war and did not want to fight.

The latter got me released in March '46 so I could return home.

I can say the French were hard on us and treated us as slaves so it was nice to leave that atmosphere. I returned to an utterly destroyed nation. I was happy to have survived the war, now I turned my attention to rebuilding. My parents fled to a friend's farm in Fulda and I met them there after much searching. We had it better than many, as we had shelter and plenty of food. We pitched in to help run the farm until 1947 when we returned to Erfurt to rebuild. Very few of my comrades survived the war and postwar internment in Russia, I was thankful for my wound.

[Above: German tanker from the 20th Panzer Division shows the camera his Panzer IV shot through the barrel by a Soviet shell during the Battle of Kursk in July, 1943.]

[Above: The Rhine Meadows Camps were a series of nineteen American death camps which murdered an untold amount of innocent German P.O.W.s.]

'April 30th was a stormy day. Rain, sleet and snow took turns penetrating... the bone cold wind swept from the north across the plains of the Rhine valley towards the camp. A deeply terrifying view appeared at the other side of the barbed wire fence: Closely pushed together to warm up each other were almost 100,000 emaciated, apathetic, dirty, gaunt men with hollow eyes wearing dirty field-gray uniforms, ankle-deep in mud standing.

Here and there you could see dirty white spots. When looking closer you could notice men wrapped up their heads or arms with bandages or men wearing merely their shirts. The German division commander said they did not eat for at least two days, and getting water caused a major problem even though the Rhine river with a high water level was only 200 meters away.'

-Other Losses, James Bacque, p.51

'My protests (regarding treatment of the German POWs) were met with hostility or indifference, and when I threw our ample rations to them over the barbed wire. I was threatened, making it clear that it was our deliberate policy not to adequately feed them.'

-Martin Brech, ex-Private First Class, in Company C of the 14th Infantry, assigned as a guard and interpreter at the 'Eisenhower Death Camp' at Andernach, along the Rhine River

'...they caught me throwing C- Rations over the fence, they threatened me with imprisonment. One Captain told me that he would shoot me if he saw me again tossing food to the Germans... Some of the men were really only boys 13 years of age...Some of the prisoners were old men drafted by Hitler in his last ditch stand... I understand that average weight of the prisoners at Andernach was 90 pounds... I have received threats...

Nevertheless, this... has liberated me, for I may now be heard when I relate the horrible atrocity I witnessed as a prison guard for one of 'Ike's death camps' along the Rhine. At first, the women from the nearby town brought food into the camp. The American soldiers took everything away from the women, threw it in a heap and poured gasoline over it and burned it.'

-Former American camp guard

Back to Interviews