Interview with Werner M., a cook for the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, Ulm, Germany, 1988.

Interview with Werner M., a cook for the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, Ulm, Germany, 1988.

Werner: Well my friend, I started my life in the HJ [Hitler Youth] and for those who chose to join this group we always had a good time. They taught us many skills like survival, sports, and health. Not everyone joined; some did not believe in it or could not afford it. I was lucky that my parents pretty much forced me into it. It really taught us how to grow into men, some of this also dealt with introducing us to the military at age 17. Only those close to graduating could go see army demonstrations on the bases. I was lucky to be able to see the SS training grounds in Munich and was left with a strong impression of the soldiers.

We were taken around the Dachau complex on a tour also; I saw some of the political prisoners which seemed in good health and spirits. I was surprised prisoners were allowed in the barracks. We were taken to the honor temples, Feldherrnhalle, and the Brown House to see the Blood Flag as well. This was in 1939 and I was 17 years old. I knew when I finished school I would go to enlist. I liked the elite status of the SS, and they were known as the elite of the movement. The men looked very smart in their uniforms, and carried themselves with a certain walk that you knew was elite and above the ordinary.

[Above: Feldherrnhalle guards wearing the rare and beautiful gorget specially made for the guards. The guard on the right is wearing the Feldherrnhalle helmet with a special decal (middle).]

Werner: I must tell you how it happened first, I feel it is important. I had family that lived in Gnesen who were all of the sudden Polish subjects in 1919. They said they were treated as second class citizens in their own land. They were forced to pay higher taxes, and the kids forced to attend schools far away. German schools were seized, and an air of revenge settled over all German communities, the Poles sought retribution for being part of the Reich. When Hitler was elected he made it a primary goal to bring back all lost lands. This angered the Poles who started persecuting Germans and even killing some who resisted or were pro-Hitler. When Germany made attempts to reconcile the problem, the Allies stepped in and goaded Poland to resist. This made the situation much worse. After a breakdown in negotiations Poland mobilized. Attacks were also happening on German territory, I know this firsthand from speaking to witnesses.

Hitler was angered and saw no other choice but to end this, come what may. We attacked Poland to put a stop to the attacks on Germans, and our territory. The Allies declared war, which all Germans saw as a black day, but most understood there were no other options.

I felt very proud of my nation and the Wehrmacht, who smashed Poland quickly. Poland had a large, well-equipped army that crumbled under the new type of warfare.

I remember being in a cinema in Ulm watching the news, and seeing the attack on Warsaw, we had the feeling of "go get em". They made towns into fortresses, but we were made to look wrong for attacking them by the English. The French dropped leaflets on parts of Germany warning the people how bad our leaders were and how we attacked a defenseless country. We knew they were lies designed to confuse and belittle us.

How did you come to join the LSSAH [Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler]?

Werner: In 1940 I was all finished with my schooling, and I had to serve six months in the labor service. I was not assigned to work on the construction of the Autobahn but as a helper in the kitchen. My family members were meat cutters and cooks, so I was put into what I knew best. I also had to help shovel dirt and do heavy tasks just so I could share that I was a hard worker like everyone else.

These road projects moved quickly so I was trained on the goulash cannon [this was a large pressure cooker ideal for quick cooking and stewing using limited amounts of energy and could operate on firewood, coal, oil or whatever combustible material was available.] that the military used. I often had to do the chore of rounding up firewood and then helping put a stew together. It was hard work, but the point was to get everyone an appreciation for the role of all workers, the motto of "walk in their shoes" comes to mind.

After my service time I was approved to join the military. I went to the SS recruiting office to fill out my request, but it took awhile to get back to me. I was summoned for the exams and had to bring family history. Himmler had built the SS into being a vanguard of Germanic bloodlines, no mixed blood was welcomed.

After going through the entrance exams I was told I was accepted via a letter, telling me when to report for training. I was going to train in the fall which I was told was best as it was not so hot. It was a happy day for me, and I went to celebrate with friends. I already felt elite, and told strangers I was now in the Führer's guard.

Times were good, we had beaten a great foe in grand fashion, and now we could relax, or so it seemed. I felt very invincible as I went through the gates of the training barracks. I went on to become a cook in the first SS with a mobile kitchen.

[Above: Left to right - Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler officer's plate (1st pattern), Waffen-SS plate and aluminum and steel utensils, cup and plates. Click to see more details!]

Werner: Yes, I was in training for the fall and winter of 40/41. I was posted to the reformed infantry regiment right after the Balkans, I was able to hear wild war stories about the fighting, and being young and foolish was disappointed I missed it. We were sent to a base in the protectorate, and my first task was I had to help prepare a reception for the Reichsführer-SS [Heinrich Himmler] that included [Josef 'Sepp'] Dietrich and all high officers. [Fritz] Klingenberg and [Kurt] Meyer were toasting the award of their Knight's Crosses. The regiment had been allotted some beef as a gift for the successful performance and we made a Greek dish that Dietrich had requested for the Reichsführer-SS to try. He had brought back some seasonings and greeted me to explain to us how to season for this dish. He had eaten it with the Italians and Greeks during peace negotiations. The whole reception went off without a hitch, it was my baptism, and the men joked about the stage I had to perform on.

I will tell you our commander was very hands on, he was everywhere among us and knew us by first name. He would often come by to ask about family and if he could help with anything. To me he was larger than life, an old guard of the Führer who fought for the birth of the movement. We had a good unit with experienced chefs and cooks who had joined up. I felt right at home, but the old hares did play tricks on us new hares. Our time in the protectorate did not last long as we were given divisional status and told we were moving to Poland to build and train. It dawned on a few that we maybe were going to take on the reds, but for most of us we thought this was a routine move. I was suspicious in June when more and more units were moving by, and I also saw more planes overhead. Rumors were that some red soldiers were caught across our border making maps. I saw more and more meetings of the officers so we knew something was afoot.

On the 22nd we knew what it was, we moved into ready positions by Krakau [Poland] and had to wait for the word to advance. I was with the rear troops, so only the frontline could see what was happening, I did hear cannon fire way off. I felt this was my big moment to live as our fathers lived in the first war. We were disappointed in that we were held back as reserves and did not move forward until July. I remember the roads in Russia were horrid, we were a motorized regiment at this time and the wear and tear on the vehicles was heavy. Russia was 20 years behind Germany. I also saw my first prisoners who looked shabby and shocked. They seemed well treated, and we even received orders from Dietrich to offer any left overs to them; we had little to give though. I was not close to the front, but I did have to endure some stray shells now and again, I remember that summer being hot and dusty. We were in the south Ukraine and I remember welcoming the rain when it came. Also the people welcomed us with smiling faces, and often offered water and small pieces of bread.

We rolled through Lutsk [northwestern Ukraine], and stopped in Shitomir [northwestern Ukraine], where for the first time an Orthodox priest came out of hiding and held an open air mass for the people, he blessed Dietrich and others. It warmed us to know we were liberating people from such a repressive regime. But we had to quickly move on and say goodbye. At this time also we had causalities; one was a friend of mine, Horst Freitag. He would be one of many who fell. The LAH [Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler] kept moving to the south with the goal of taking the Crimea and moving into the oil fields. We were able to keep our company fed, but it was hard as supplies moved slow. Sometimes the Luftwaffe had to drop food to us.

[Above: Germans being honored in a Ukrainian Orthodox church ceremony. This happened all over the Ukraine and Russia.]

Did you ever witness any war crimes?

Werner: Yes I did and strangely enough there is not a word of these today. From the very first days of the attack, German soldiers who had surrendered were found shot execution style. While eating a lunch I overheard Dietrich and our officers discussing that the Russians were not taking any prisoners, and if orders from Stavka [The Stavka is a name of the high command of the armed forces formerly used in the Russian Empire and Soviet Union and currently in Ukraine.] were involved.

Orders were given that any political officers were to be held back, but all others were to be taken prisoners and sent on, this went out to us all. There were German soldiers murdered in Broniki, outside Lutsk, they were stripped naked and shot down. This happened at several places, yet our forces still took prisoners despite this. I knew of no instances where we refused.

The whole east front was marred by occurrences like this, we found many towns where the retreating reds killed the people, burned down their homes, even killed their animals. These were their people, and we could not understand, but the people explained to us the reds hated the Ukrainians and wanted them dead.

I will also say we saw many dead Jews, and I will explain. The Jews favored Marx and built the red terror, killing many who opposed this. When they lost the protection of the red army, the people rose up and killed them, their vengeance was unmerciful. I understand some police units joined to execute those who were pointed out as killers.

It was dreadful to see, however it must be looked at in the context of the times.

Jews actively aided the reds in suppressing rights, and turning in people to be removed. Synagogues were allowed but churches were heavily taxed and controlled, only those who preached Soviet praise stayed open, all others closed. When German units were close by, the people formed militias, armed with tools and knives and the Jews paid a heavy price.

Regarding the Jews, I will tell you a secret. I had a friend who lived on our block; he went to Berlin to work in the SD [Sicherheitsdienst was the intelligence agency of the SS] in the office of Jewish resettlement. He told me once that all Jews in the Reich had to state their racial makeup, full, part, or converted. Those who refused were the ones sent away to camps, later in the war more were removed for threat of espionage.

He went on some of the roundups and said they were done very politely and with Jewish sensibilities in mind. Many, many Jews were allowed to stay in the Reich, I saw them, and they were left alone. Only those who were thought to pose a threat or refused to announce their genetics were removed. This ties into war crimes as our enemies say it was a crime, but most nations did this to untrustworthy minorities in wartime.

How did you view the civilians, and did you get along? I understand in Italy there were bad problems?

Werner: I do not know of this, I can tell you in Russia and wherever the LAH was, we got along well with the civilians. I can show you photos of the many people who we ate with, lived with, and protected. The Ukrainians saw us as liberators, and we wanted to live up to that.

Dietrich gave a speech to each battalion in the beginning. He said we are entering this crusade as the liberators of the people, and said we must treat them as friends, not enemies. He welcomed them into our camps, we still worried about spies, but the Ukrainians hated the reds. A boy would always come and ask for food for his sick mother. A medical orderly saw this and brought the mother back with him to be treated. We never turned away the civilians.

We had many helpers who were ex-prisoners, which you may find odd, we called them Hiwis, and they did everything from cooking, sewing, cleaning, and watch duty. We often ran into the Ukrainian militia which would report to our leaders on enemy activity. They would bring sick and wounded to our medical unit to be treated.

Our regimental doctor was killed by partisans after venturing off without escort, to deliver a baby several kilometers away. That should say something. We went out of our way to be friendly and helpful; cooking for the people, chopping wood, even helping them rebuild huts. The reds destroyed a lot in the beginning, we helped rebuild.

Even in Italy when the LAH was sent there to prevent an Allied invasion the people greeted us as heroes. They were very loyal to Il Duce [Mussolini] and thought of us as allies still. They made sure we had good rations to cook with at a time when supplies were still catching up.

I know the recon units ran into some fights with red partisans, but that was rare. Our time in Italy was spent taking leave, training, and relaxing with the locals. I do not think the partisan war is that big, I think it is overstated today to portray a people's uprising that never occurred.

Sure there were small limited attacks but they were rare and far between. Now, later in the war, in late '44 they picked up as the Allies infiltrated units behind our lines to carry out attacks, and red partisans did flood into the protectorate in April '45. It was not the frontline soldier's duty to fight or deal with partisans, unless they directly attacked.

The police, militia, or units specifically assigned to deal with the rear areas only dealt with the partisans. I only saw the result of a few hangings by our division, and it was people who directly took up arms as combatants and killed or injured soldiers.

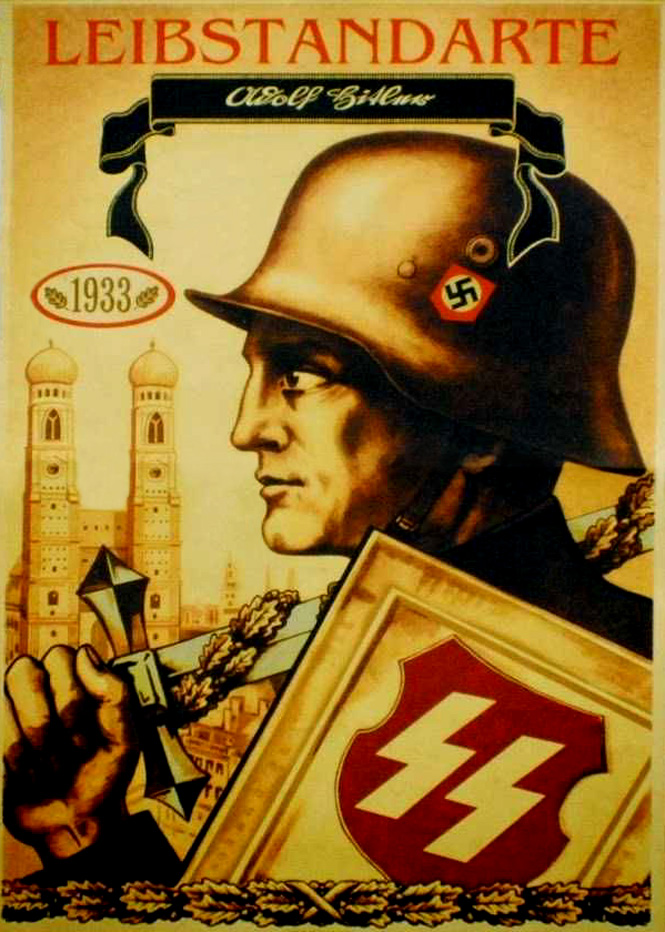

[Above: Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler postcard.]