Interview with Josef Biehl, former SS man at Dachau and later Wehrmacht veteran serving in France and Russia. Nuremberg, 1981.

[Tante Inge translating/helping]

Interview with Josef Biehl, former SS man at Dachau and later Wehrmacht veteran serving in France and Russia. Nuremberg, 1981.

[Tante Inge translating/helping]

Josef: Yes, indeed my friends, it was the right thing for me at the time. Back then to be in that uniform and to have SS membership was a high step in life. You were seen as belonging to a loyal and faithful group of men. I was looked upon as being in the elite of the nation during that time. Now my story did not start in the SS, let me tell you something you do not know, I am sure, but you need to. I come from Pilsen, in what is now Czechoslovakia. I was there when the crisis happened and will share my experience. I was slightly older than you when there were problems with the area I come from. It was settled by Hitler and in 1938 I was able to join the SS TK Standarte [Totenkopf] which was assigned to the Dachau area. I remember my parents were willing participants in this endeavor as they wanted a quiet house for sure. I applied, went through the process of testing, and was granted conditional membership. I was off to Munich, and before coming to the training grounds we were all taken to the important sites of the time. My oath to the Führer was on the 9th of November.

I saw the camp very well, as all TK units were trained in the training units which were close to the camp. I saw the prisoners in the camp, and I can assure you they were treated very well. They had very strict rules and a schedule they all had to follow, but never abused. I even saw a ceremony where some prisoners were being released. Yes, they even let prisoners go when they served their sentence, it was a prison for political prisoners. If someone committed a crime, and it was based on a political motive, they went to a camp instead of jail. In Germany of that time there were laws in place to keep communists and anarchists from rioting and harming the nation. For a short while I was assigned to the office that read their mail to make sure it was not discussing anything that could harm the nation or Hitler. I was surprised that so many of the prisoners were against the Hitler regime, at the time it was very good and nothing bad had happened. They were largely old reds, even the church people there seemed to hold Bolshevik beliefs.

I remember seeing a letter from someone famous, who I can not recall now, but the person writing him would tell him that his beliefs were protected by his god, and for him to keep the faith that good will always win. I knew what that meant, but let it slide. Remember nothing bad had happened yet, yet these people believed the regime was bad and wrong, I did not understand how they could feel that way. I knew there had been the removal of what was called unqualified people, many of them Jews, from certain professions. It was believed they attained positions based on being Jews, whom other Jews helped, and did not obtain them honestly. The churches had some left-leaning clergy who spoke out for the reds and Jews, and they were removed as well. This, in my opinion, was very correct, and not worthy of ridicule. I was back then a firm believer in Hitler and thought anyone opposing his worldview was a fool or deliberate criminal. Hitler restored German honor, fixed the economy, retuned morals, and gave us all a sense of hope for the future. It was a great time to be living in, but, again, I did not understand why some did not want this.

Today they get to tell their views and their stories that make it all look so bad, and the believers look evil. It was just not so, at least in the areas I saw. Everything was happy, productive, and moral.

I wore the black uniform back then with the death's head on my collar. It was nothing bad and looked upon as honorable to the past of Germanic Germany. I agreed with Himmler on his views of the SS and what it meant for Germany. I had to prove my ancestry was pure German even to get in.

They made you feel very elite, and belonging to something related to the old past that was being pulled into the new time. I never saw anything corrupt or evil during my service time in the TK Standarte. I even met [Theodor] Eicke who today they say was very evil and cruel. I saw none of that, he was a very friendly and proper leader.

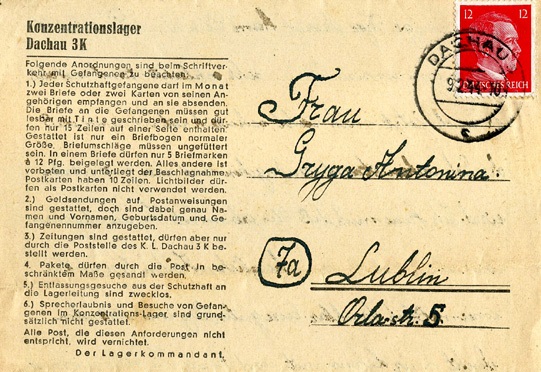

[Above: (left) A mailing form/letter from Dachau postmarked on February 9, 1944 and sent to Lublin, Poland. On the left are rules for the inmate to follow when sending letters. Click to see the full letter.

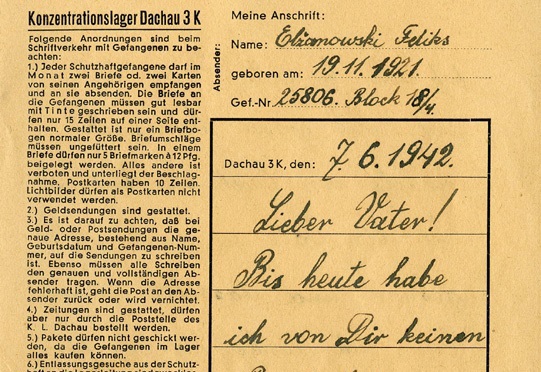

(right) A different type of Dachau mailing form sent June 7, 1942. Click to see inside both and for translations.]

[Above: (left) An envelope from Dachau sent September 9, 1939 sent to Vienna. (right) An envelope from an SS guard in Dachau sent June 19, 1942.]

[Above: The mighty Theodor Eicke, who led one of the most effective divisions on the hellish eastern front. He fell in battle on February 26, 1943, an eternal martyr in the fight against darkness.]

Can I ask you why the SS used a skull? It seems evil and bad like in comic books they show it as evil devil worship.

Josef: Oh, heavens no young one, it was simply a testament that the SS was loyal unto death, meaning we must be ready to lay down our life for our people. That is the best explanation I can say to you, it also could be said it meant we did not fear death. We wore it with pride as it meant we were loyal, and that our honor was our loyalty.

We wanted any enemy to know, a fight with the SS was fighting men who did not fear dying. And so, we would fight like lions, that was all this symbol meant. I do not know the books you speak of but be careful where you get your information. If it is wrong, you will think and understand incorrectly.

Were you in the war? What did you serve in?

Josef: Yes, I was in the war from an early time in 1940. When war broke out, I followed my family line and enlisted into the army, in the artillery branch. I had to petition to leave the SS, and they made it hard. My commander even chastised me, as the Waffen-SS was being formed. I respectfully told him my duty was serving my family line so I was made an army NCO as an observer. I trained until April of 1940, and then it was time for France. And so, I was part of the breakthrough at Sedan and saw the fighting up close.

What did you think of the French?

Josef: I must tell you our people have not liked each other, it all started with clashes with royal houses, and then Napolean. It was settled in 1871, and then resettled in 1919. When Hitler came to power he had no hate for the French, and relations had warmed it seemed. That was until Poland.

Britain urged the war, and France followed them. They declared war on us and in May of 1940 we attacked France to force the issue. When we broke through, we immediately started seeing French and Belgian refugees, they moved slow, and we moved fast. I remember they slowed us down at times, some thought this was done on purpose.

We had to make them get off the roads so we could have freedom of movement. Our battery would set up for action, many times close to a town. If people were still there, we urged them to leave in case there were attacks. I want to tell you as well, to clarify, we were never allowed to set up in or around a town just for that reason. War tends to involve civilians who want nothing to do with the fighting. Shells can go astray and at times took the lives of French civilians.

The war on France was fast-moving and it lasted only a short time, we ended up being in the South of France until the demarcation line was made. Then we stayed for the summer and enjoyed the warm weather of the coast. I remember that things were settled down and we helped the French put things together again.

I really liked the French, I found them to be friendly and eager to do business. We had money and enjoyed the fruits of victory. I have nothing bad I can say about the people of France. It was sad that we had to go to war against each other. We meant no ill will towards their nation. Now, the resistance people I have no respect for, they were killers and terrorists, who today seek praise and hero status.

[Above: (left) German soldiers collapsed exhausted on the side of the road. The blitzkrieg was so fast and grueling it left the German soldier tired beyond imagination. (right) Some slept forever in beds of French soil.]

[Above: (left & right) A ragged, cool-looking German soldier poses beside French civilians.]

[Above: (left & right) Ruins in the coastal city of Dunkirk in northern France.]

I understand you fought on the Russian Front, can I ask how it was and where you were?

Josef: Yes indeed, I was in the east. It was in 1941, I marched into Russia thinking we would have an easy time of it. I believed what our propaganda told us that the Russians were poor and had no will to fight. They were wrong in this. I was part of what was called Army Group North, and we went through the Baltic states to Leningrad.

We broke up Russian defenses and then moved forward, and repeated. I remember there were kilometers of nothing there. We could travel for a day and not see any towns or villages. It felt very empty, I remember thinking. We ended up as part of the ring around Leningrad.

We laid siege to the city to try to get them to surrender, but in one of the strange twists of war, it was not really a siege at all. We held the southern ring around the city, but they were able to keep the city supplied due to problems with the Finns. We sat on our asses and had only sporadic action in repulsing Soviet attacks either on us, or to break the ring.

I do not know much about Leningrad; can you tell me about why there was a siege? Why were there problems with the Finns?

Josef: Oh, the Finns, they were a hindrance to us and were not in the war on our side it seemed, some ally. Hitler wanted to take Leningrad as it was a very large city, and bore the name of Lenin, a founder of the Soviet state. When we moved into Russia, the aim of [Army] Group North was to take Leningrad and push on past the big lake there.

We again had to deal with masses of civilians and the very bad roads. Stalin had very poor roads, and no technology to build them. They were nothing more than dirt tracks, and when it rained we were slowed to a crawl at best. I remember that well from my time in the east, it was very poor and backwards.

It was not worthy to be called Europe, and I blame the reds and their Soviet system, they kept the people in poverty and ignorance. Let me tell you both this, when we went into Russia proper the people who stayed behind welcomed German forces as liberators, not as enemies.

Stalin and his hordes used old tactics to burn everything down. They poisoned wells, destroyed dams, burned fields and towns. They wanted to leave us nothing, and they unloaded many people on us who they could not or did not want to take with them in retreat.

We really had a hard time with food that winter, it was very cold and there was no shelter in some areas. Add to that there was no food or safe water, and it was very bad. We had to build very fast cabins and huts that soldiers and civilians both had to live in. I had to help with this as well as maintain our artillery positions.

I was an observer that winter and had to stay out in the cold for hours watching enemy movements. I could call in for a mission to fire on the Russians. The Finns only pushed the Russians back to pre-war borders, so they did not have an interest in Leningrad. There were small corridors the enemy opened and would pour in supplies before we could organize to attack them.

As I say, it was not much of a siege, it was more of a 'hold our lines' to resist the Soviet assaults. If the Finns had helped us more maybe we could have taken the city. The Finns only wanted to move to the pre-war borders and refused to move further into Russia. They only wanted land they lost to Russia as their war aim. They were too short-sighted in this, as the problem was much bigger.

It was a point of contention with them, and to top it off they declared war on us in 1944 while making peace with Stalin. Many refused to fight German units, but a few units did and brought hard feelings from Germans. I don't have anything against them, but they did not help Germany in our time of need. Our commander even asked for supply help, and they refused, instead asking us for supplies.

Maybe they really did not believe in the war. We had to attack Russia see, I know Hitler believed Stalin was going to attack, which they will never admit. I saw the large supply bases they had in the Baltics, and they were not used to feed the people. Everything I saw was of an offensive nature, not defenses as the Soviets had maintained.

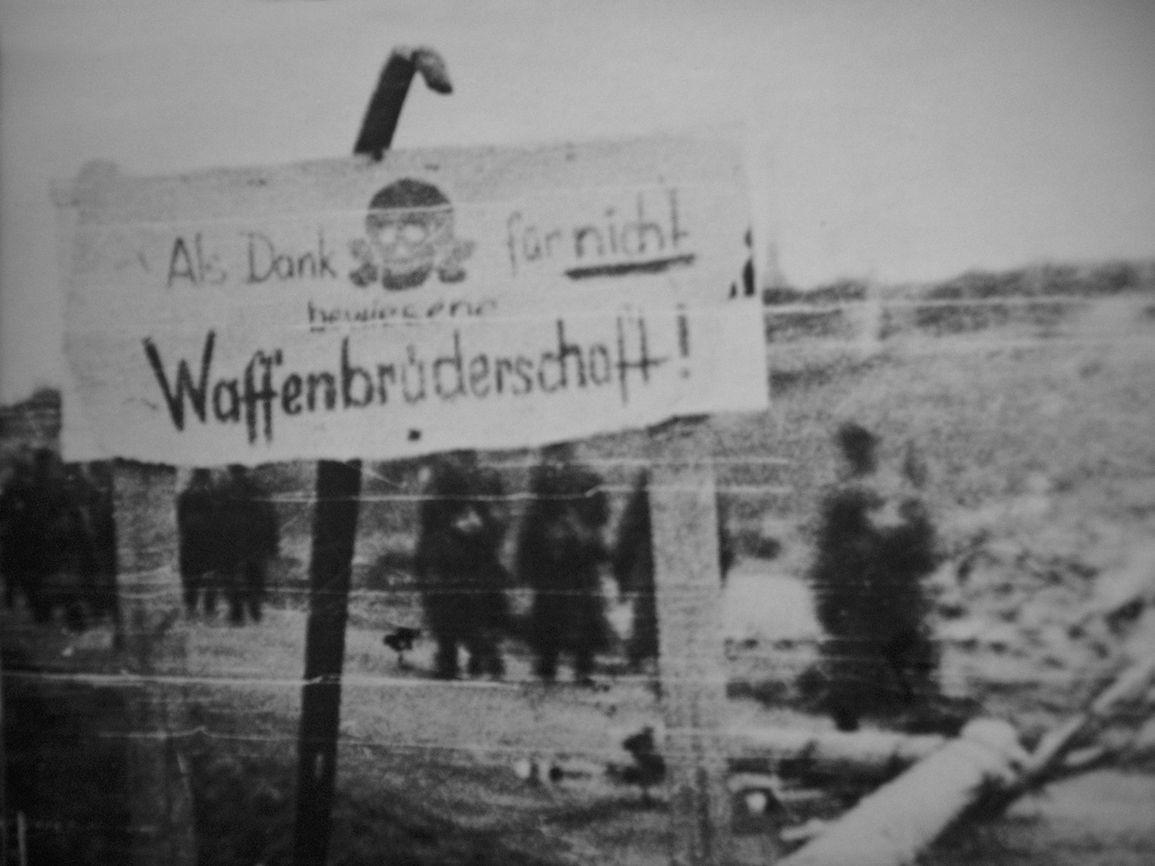

[Above: A bitter sign the Germans left in Lappland in 1944 after the Finnish government betrayed them. It translates into something like: 'In gratitude of brotherhood-in-arms NOT demonstrated.' But we must not forget about the thousands of Finnish soldiers who refused to turn against their German comrades and went with the German soldiers. Many of these incredible brave men would die in the final battles at the end of the war.]

[Inge question] Let us ask about the siege itself, today the media touts the story that the siege was a deliberate attempt to wipe out the city and kill all the civilians. A monument was just built, and East German news has said 2 million were killed. Even our press here agrees and does not challenge Soviet figures. Would you agree with these numbers?

Josef: I must say with honesty, no, I feel the Soviets have lied so much about the death numbers they give. I know that before we arrived around the city, they moved a large amount of the population away to help the war effort far away. Military units fortified the city and forced many civilians to fight as well. We saw many deserters come to us, who spoke of this and gave us valuable information.

This land was very damp and miserable to stay in, we had corrugated iron sheets as shelter. And the civilians were forced to move back but many still stayed by us as they had nowhere to go. It the summer the flies and mosquitoes were the main enemy.

Although war is war, it is not true we were told to target civilians with our guns, in truth we rarely shelled the city after the first couple months. We hoped they would just give up if we pushed the red army away. That never happened so the city was able to stay in the battle. They went on as in peacetime it seemed, they played music for us as well, to rub it in that they were okay.

Again, it was war, at times we shelled the defended areas as best we could, and at rare times the Luftwaffe bombed strong points. Our war aim was to let the defenders know we would not go away and they needed to surrender. I never saw a battery just free fire on the city or target hospitals including civilian areas. More than anything we were used to fire on the roads and assembly points the Russians were using to attack German positions.

I would see through the range finders into the city, and there was a lively population there, it is true. However, I also believe the Soviets got out any essential people they wanted and left only the old, infirm or less useful. Damn it, these rascals even released all the criminals and sent them our way. They kept the police units busy trying to filter out who was a political prisoner that would help us, or a real criminal who had to be put away by us. There were thousands of them, and I do not believe it is a coincidence that the partisan bands started up in this area in 1943.

I think it is more honest to say that due to lack of food, the cold weather, natural causes, and either bombing/shelling that under 50,000 died. I am admittedly no expert on this and am only using deductive reasoning, but I think that sounds reasonable. I feel that many names on any monument you speak of may have been invented or added when it should not have been.

The Russians have wanted to portray us as being strong, impregnable invaders to make their victory seem glorious and against the odds. I must take that from them, as it is untrue. Let me say this also, our divisional doctor was able to go back to Russia in 1955 to help returning prisoners. He gave a talk about this at our korps reunion.

He admitted he was bothered by all the stories coming out in the papers about how bad German forces had behaved in the east. He was granted papers to tour areas we were formerly in; he spoke to the people as well. He said of course some would not speak, but he did find a small few who in confidence told him there was nothing to the Soviet stories of mass killings.

They confirmed to him also that the German military behaved quite correct in the east. This is of course something those of us who were there knew, but he was able to go all around. He let us know that, of course, some convinced reds tout these stories and embellish them, which the media loves. But the normal Russian lived with us in peace and had nothing to fear from us.

Many also joined us in the fight, I know we used many former prisoners in our positions. They helped the civilians who escaped the city later, the Soviets refused to allow anyone to leave. They manned food places, hospitals, and supply areas. So, you see, it is not all that it seems, today the truth is not told.

Did you see any actions against the Jews in the east?

Josef: No young one, I also do not care to talk about the Jews. We can feel sorry they were put through what they were, but at the same time, I think they may be playing too much the victim. Here it is not polite to discuss them, so I do not. I will say I did not see anything in the east that was bad against the Jews.

How did the war end for you?

Josef: That I can talk about, and I was both fearful and grateful. We rotated on and off around Leningrad, and I returned to the east in 1943 during the winter, after training. I was there during the battles that pushed us away from our ring. By 1944 we faced a renewed red army that was rebuilt and outmatched us by far.

I remember a pamphlet they dropped on us; it spoke of Hitler handing us Iron crosses while Stalin handed his soldiers mortars. We felt this as well, they seemed to have an unlimited supply of both mortar and artillery shells. When our lines broke, it was a slow fighting withdrawal as best we could.

We would move back and set up a position, firing on what we could. By this stage our supply system had improved, but there were not enough shells to go around all the time. There might be a day where we could not fire as another unit received the shells, and vice versa. We were pushed out of Russia, the Baltics, and Poland by the end of 1944.

I was wounded in March of 1945 by Russian planes bombing our position. I was moved close to Berlin and captured by the Soviets. I was lucky in that I had a sympathetic nurse who helped me escape when I knew I could walk. Soviet soldiers were guarding us, as they did not remove those who were badly wounded. I remember having a bad feeling about them.

I could not stand or walk when they came, and they tried to force me, but me falling on my face convinced them. I was told to make my way west to the Allies, as the Russians were punishing anyone they captured. I walked at night, by myself, and would hide on farms. I stole eggs and food to keep me going.

The Russians had patrols out looking for stragglers and I avoided them all. I made my way south but ran into people who told me the partisans were bad in my former land and have killed many Germans. I turned west and made my way to Erfurt where I was quickly arrested. Lucky for me I had kept my hospital papers, so I was sent to a hospital to get checked out, and then was put under arrest.

I was very lucky in that my time in the SS never came up, I was a low rank and was not in very long, asking to be dismissed for war service. This helped me and I did not go into the Waffen-SS as my family felt the regular army was more professional and equipped. The fate my comrades suffered is a shame and is quietly remembered.

And so, I was released after only a couple of months and went on my way. I was on my own, and I never found any of my family. As best I can tell, they were killed by Czechs, partisans, or the winter cold during the march west. It is a sad chapter in my life, but the end of the war also was a new beginning. Now we pray for peace and hope no bombs fall on us.

How do you like Germany today?

Josef: I love my land, but I hate what we have become. Inge can tell you about the flood of Turks here. They came here after the war. While one would expect that if you were moving to another country you would be asking "what can I do to help this new home of mine?" Not for the Turks, or any other eastern peoples, they seem to have come only to exploit and feed off us.

We must pay taxes to keep them fed, and they breed like rats. They are mostly the poor kind who have nothing to do all day but eat and screw. The one downstairs has 6 kids, while a German woman will only have one or two at most nowadays. Himmler saw this, I remember reading a book in the Dachau library about the overtaking of Germanic blood.

This is now happening here. These people come to our land not to help us, not to say "hello, I see you are in need, may we help you rebuild?" No, they come to take and steal. They are always in trouble with the police and the worthless politicians nowadays do nothing about it.

In 50 years, we may not recognize Germany if they do not stop this madness. We only go to help build up areas and countries, then we leave or settle in if the people will have us. But here it is different, look at France now, the south is being taken over by the Africans they bring in, who live off charity.

I have to say also so you don't report me, I have no hate towards them, but they should not be allowed to stay here and live on welfare while they breed.