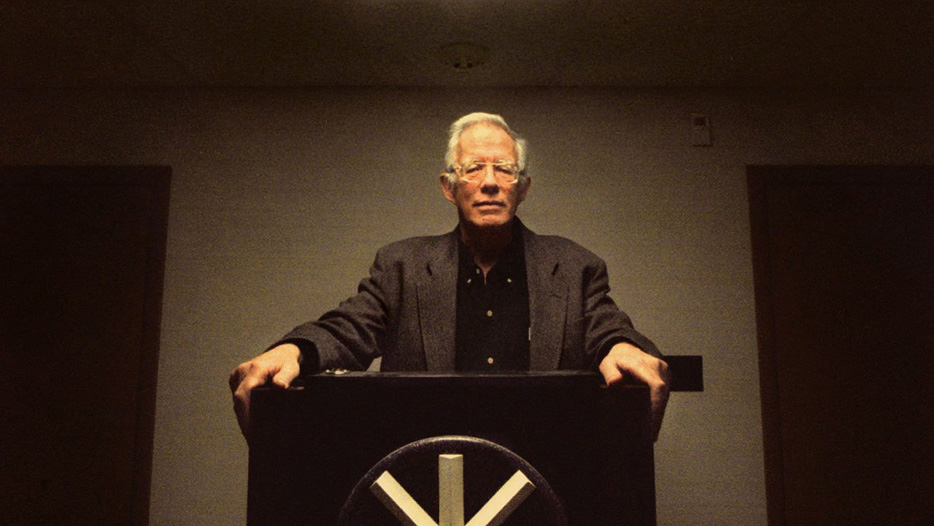

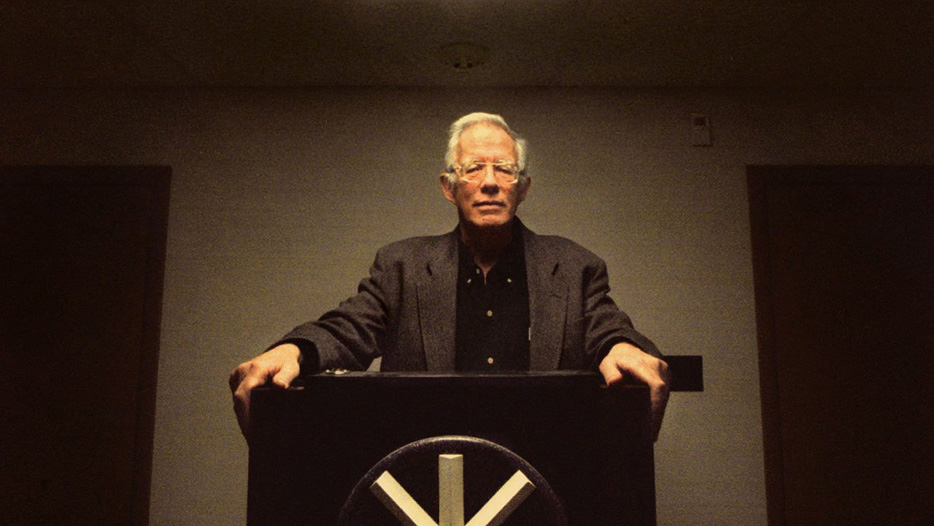

George Lincoln Rockwell

By Dr. William L. Pierce

George Lincoln Rockwell

By Dr. William L. Pierce

I first contacted George Lincoln Rockwell in 1964. At the time I was teaching physics at Oregon State University and I was beginning to wonder what in the world was going on as the turmoil and chaos known today as the “civil rights revolution” got underway.

I didn't quite know what to make of it when my Jewish colleagues would ask me to sign petitions demanding that the university hire Black faculty members and recruit Black students.

Then one day I saw a short television news segment of Rockwell trying to speak to a group of students at a university in California, while Jews in the audience screamed at him and threw bottles and stones. I heard only about two sentences of Rockwell's speech, and then the Jews rushed onto the stage and ripped loose the cable from his microphone. That evening I hunted up Rockwell's address in the library and wrote him a letter.

Two years later our correspondence had grown into full time collaboration on my first magazine, National Socialist World, and the year after that, Rockwell was gunned down by a hate-crazed assassin.

In 1964, when our relationship began, Rockwell was a 46-year-old publisher of a monthly newsletter he called The Rockwell Report and the leader of the American Nazi Party, a small group in Arlington, Virginia. In early 1966, shortly before I moved to Virginia and began publishing National Socialist World, he reorganized his group as the National Socialist White Peoples Party.

He had been a philosophy student at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island before the Second World War. After war broke out in Europe he joined the Navy, became a naval aviator, and rose to the rank of commander.

After the war he studied art, and then began a small advertising agency when he became concerned — five or six years before I did — about the growing influence of communist ideas and policies in America.

He associated himself briefly with various groups and individuals having a conservative, patriotic orientation. All of these were afraid to deal openly and forthrightly with the two issues that Rockwell soon came to realize were at the core of the problem: race and the Jews.

Anti-communism wasn't enough, he decided. One must attack not only the symptoms of the disease but its cause. One must expose the Jews as bearers of the communist virus, and one must also understand that the great danger posed by the Jews is not that they generally favor leftist economic or social policies, but that they aim at destroying us through racial mixing.

By 1959 he had concluded that traditional conservatism was more of an impediment than an aid to the struggle against the Jews, and he declared himself a National Socialist. Actually, he declared himself a "Nazi," began wearing a uniform with a Swastika armband, and greeted his followers with the Roman salute and a "Heil Hitler!"

This touch of Hollywood in Rockwell's approach to revolutionary politics always was a bone of contention between him and me. I argued that the uniforms, flags, and theatrical behavior — even the name "American Nazi Party" — made it difficult for serious people to take him seriously. His medium got in the way of his message. He replied that if he put away the flags and armbands, wore a business suit, and shunned theatrics, the news media would ignore him and no one would hear what he had to say.

His aim, he said, was to make people pay attention to his simple core message of the need for rebuilding a White, Jew-free America based on the principles laid down by Adolf Hitler in Mein Kampf. When he had tried to present that message in a sober, serious way, no one had paid any attention to him. The newspapers and television stations wouldn't send reporters to his press conferences, they ignored his press releases, and the public didn't even know he existed. But as soon as he raised the Swastika banner, the news media went crazy and swarmed all over him. He was seen on all the TV channels and what he said was reported in the newspapers.

Yes, I answered, the theatrics get attention for you — but your message gets badly distorted. The media try to make you look like a madman and a clown, and to a large extent they succeed. The result is that most of the people attracted to you are losers, social outcasts, freaks. If you want to attract winners — serious, competent, idealistic people — you need a serious image.

Rockwell responded that it is the losers, the social outcasts, who make up the ranks of every revolutionary movement. They're the ones who are available, the ones who don't have anything to lose by becoming associated with a politically incorrect cause.

Individually they may not be very impressive but large numbers of them, organized and disciplined, would make a revolutionary army. He had tried appealing to what I called the winners: to the teachers and professors, to the doctors and lawyers and engineers, to the writers and artists, to the businessmen and the craftsmen, to his fellow military officers, to the careful, responsible men and women with steady employment and stable families. And he had found that while many of them agreed with him in principle, almost none had the moral courage to stand up and be counted among the righteous.

He had given speeches to groups of these people under the cover of several ostensibly conservative organizations. They would come up after his speeches, shake his hand, and tell him they admired him for saying what they also felt. But the merest suggestion from Rockwell to one of these people, that he ought to participate in an effort to take America back from the Jews and their collaborators would send the fellow scurrying away in fright. They were too comfortable, too corrupted by good living and materialism, too unaccustomed to taking risks and facing opposition. Only in the masses, Rockwell had finally concluded, were the recruits to be found that he needed to launch a political campaign to take America back — and the masses could be reached only through the mass media.

I still had serious doubts as to whether the type of people Rockwell was attracting with his flamboyant tactics could be disciplined and used to build an effective organization, and these doubts made me hold back from a whole-hearted support of his efforts. We collaborated on the publishing of National Socialist World and we continued to argue about other things. I gradually found out, however, that Rockwell was dead right about the moral cowardice and the servile conventionality of the great majority of Americans. Most of them would rather lose an arm and a leg than be suspected of thinking a politically incorrect thought, and as I worked and argued with Rockwell, my appreciation of his own courage and idealism grew.

He was a man with several talents, any one of which could have earned a comfortable living for him. But he was also one of those rare individuals who is wholly in contact with reality, who wholly identifies with the world around him and who, therefore, is incapable of ignoring what he recognizes as wrong. To Rockwell, evil must be opposed; good must be upheld. To pretend that the world is other than it is was self-defeating. To lie about it or to try to fool others about it was unthinkable. Once his eyes were open to the Jews and what their policies were doing to America, there was no question of keeping his mouth shut and going on about his business. He had to speak out against them. He had to fight them. He would fight them anywhere, anytime, under any conditions, no matter what the odds, and he would fight them with all the strength of his being. I'm sure that if there had been just a thousand men like Rockwell in America in 1966, we'd be living in a healthy, progressive, all-White America today.

Like all of us, Rockwell had shortcomings, of course. He was sometimes mistaken in his facts. He thought Pablo Picasso was a Jew, for example. He sometimes misjudged character in people. He had a tendency to oversimplify things and I'm convinced, more than ever, that both his theatrical tactics and his strategy of trying to persuade the masses before recruiting an elite cadre and building a strong infrastructure were unsound.

His evaluations of the basic moral health of America and of the intelligence and character of the American people were far too optimistic. He really believed in 1966 that the Jews and their collaborators could be beaten by 1972. His optimism fueled his activity and he eagerly sought opportunities to carry his message to anyone who would listen.