'For the seventh time, I have the pleasure of opening an exhibition which affords us insight not only into the workings of one of the most important branches of industry in our country, but also of a large part of the world.

Within the framework of the Four-Year Plan, we sought to free motorization in Germany from dependence on factors abroad and to establish our own independent raw material base. After only a few years, the results of this effort may today already be called gigantic. In part, they have led to overwhelming new inventions whose superiority renders it unnecessary to use raw materials formerly [involved in the production process], even should they be abundantly available once more in the future.

In an overview of these facts, which in themselves reveal to us the greatness of the results attained, we note the striking evidence of the gigantic increase in production, the extraordinary rise in exports, the lowering of prices for certain models of automobiles and motorcycles, and above all, the excellent work in detail. I open an exhibition today which will splendidly demonstrate these achievements. In spite of this, along with a few smaller tasks and current problems, there remain great tasks yet to be accomplished:

1. It was understandable that, in times of grave concern for sales, each individual firm, more or less nervously, tried to scan the market and its requirements. Hence, as I already pointed out in my last speech, each firm seized that model which apparently held the greatest promise, without considering how many other factories were already involved with this particular model, or the potential size of the series already in production at any one factory. The resulting competition precluded a potential decrease in prices for certain models. Furthermore, it was understandable that, under the circumstances, a relentless competition for customers ensued which led to an exaggeration of the mechanical element. This meant the incorporation of any type of innovation in the car, no matter how insignificant its practical application, simply because of the belief that one had to oblige a highly selective customer.

The conditions which led to this technically and economically undesirable phenomenon no longer exist today. It is less the task of today’s German automobile industry to seek potential customers than to satisfy the demands of existing customers. The demand for automobiles is overwhelming. The following are necessary in order to satisfy this demand:

a) Lower prices. This is possible in the long run only if one instills order in the types of models produced. This means that individual firms must achieve a consensus on the type of models to be produced and restrict the overall number of models. Indeed, there must be a simplification of the production program to very few models. It is crucial to augment the total production of automobiles instead of increasing the number of models offered. The multitude of these would ultimately lead to a splintering off into an infinity of models, encumbering the production process and possibly lowering total output.

b) Justice can be done to this call for lower prices only if the weight of cars, particularly of those in mass production, is significantly lowered. Every kilogram of steel needlessly tacked onto an automobile not only raises its costs and its retail price, but also maintenance expenditures. This in turn leads to more gas being used up, tires wearing out more quickly, and street surfaces needing more frequent replacement. Moreover, a 3,000-kilogram automobile performs no better than one in a 2,000-kilogram category, but needlessly taxes the raw materials at our disposal. Two cars in such a heavy weight class simply rob us of the materials needed to produce a third one.

I do understand that, in the end, the industry was not capable of arriving at such an ordering of its production on its own. Therefore, I appointed Colonel von Schell as plenipotentiary to see to these tasks being carried out. He is presently issuing binding directives to all appropriate offices within the framework of the Four-Year Plan. His activities have already resulted in exceptional results and hold great promise. He will be in a position to account for his activities for the first time at the 1940 exhibition. The resulting further decline in prices for our automobile industry will undoubtedly have a positive effect on exports.

2. Let the new Volkswagen represent an enormous, real avowal of these principles. All those concerned are called on to devote the greatest energy to press forward the construction of its factory. I sincerely rejoice in being able to afford you a glance at the car for the first time in this exhibition. The Volkswagen’s ingenious designer has bestowed an object of extraordinary value on the German Volk and the German economy. It is up to us now to persevere in our efforts to shortly begin mass production of this car.

3. The pending increase in the flow of motorized traffic, due to the Volkswagen and the introduction of a series of low-price trucks, now forces us to take steps necessary to ensure traffic safety. In a period of six years, the German Volk sacrifices nearly as many men to automobile-related accidents as it did in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. This cannot be tolerated. Though the beneficial cooperation of State and Party offices, and the deployment of traffic police and NSKK patrols has already brought some relief, these results can neither be regarded as satisfactory nor can the situation be regarded as tolerable.

Above all, there are certain principles and duties all those who participate in traffic on German roads must be aware of: When someone causes an accident today, whether he be the engineer or the switchman, then the responsible party will be regarded as an unscrupulous criminal who is indifferent to the life of his contemporaries, and he will be punished accordingly. The driver of a private vehicle bears similar responsibility not only regarding his own life, to which he may be indifferent or which may be of little value, but for that of other participants in traffic.

Whoever nonchalantly endangers these lives acts in a criminal manner and without any scruples.

Those who cause the nation to lose 7,000 men annually, in addition to imparting to it the care of 30,000 to 40,000 injured, are parasites on the Volk.

They act irresponsibly. They shall be punished as a matter of course, provided they do not escape the Volksgemeinschaft’s wrath by dying themselves.

It is truly not an art to drive fast and to endanger the lives of others. Rather it is a great art to drive safely, i.e. carefully. Lack of caution coupled with high speed is the most common cause of automobile crashes. And it is discouraging to realize that the majority of those driving could easily spare the extra ten, twenty, or even thirty minutes which, at best, they can hope to save by their insane reckless driving (Wahnsinnsraserei), even on long stretches.

This constitutes a call for all those involved in the training of our drivers.

One should point out that the new roads in Germany, especially the Autobahn, distinguish themselves in allowing for a high average speed, although peak speeds may well be relatively low. The Reichsautobahnen were not built, as many mistakenly believe, for a speed of 120 to 140 kilometers per hour, but rather for an average, let us say, of eighty kilometers. This is easily obtained by driving at a near-constant speed. In the end, this speed over long distances far exceeds that of even our most rapid trains.

Speaking on a matter of principle, it is indeed un-National-Socialist behavior to be inconsiderate towards other Volksgenossen. At this point, I would like to say today that I expect, in particular of representatives of National Socialist institutions, that, in this realm as well, what otherwise would be mere lip service to the Volksgemeinschaft, will become a matter of course for them. Besides, in the context of our national supply of raw materials, it is absolutely senseless to drive at speeds which increase the rate at which tires need replacement twice or even three or four times. Naturally, these speeds also cause an uneconomical fuel consumption. In general, our race cars and their drivers set speeds and records for performance, as do others who promote motorization. They do not need the support of more or less talented amateur drivers. Consideration for one’s fellow man should have priority for all those on our streets; otherwise they cannot expect the Volksgemeinschaft or the state to show consideration to them. All of us should unite to make our country not only the one with the greatest traffic density, but also the one where traffic is the safest. In the interest of maintaining this traffic safety, the state stands determined to mercilessly destroy and exterminate those criminal elements which set up road traps and rob taxi drivers, and commit murder.

I wish to take advantage of today’s occasion to thank all those who have not only contributed to the domestic significance of the German automobile and motorcycle industry, but also to its renown worldwide: the businessmen for their enterprising spirit; inventors, engineers, and technicians for their ingenuity; and masters of their trade and laborers for their astounding achievements. The German Volk today can justly be proud of the marvels of an industry which once took its first, gingerly steps toward practical application in this country.

In this spirit, I hereby declare the 1939 International Automobile and Motorcycle Exhibition in Berlin open to the public.'

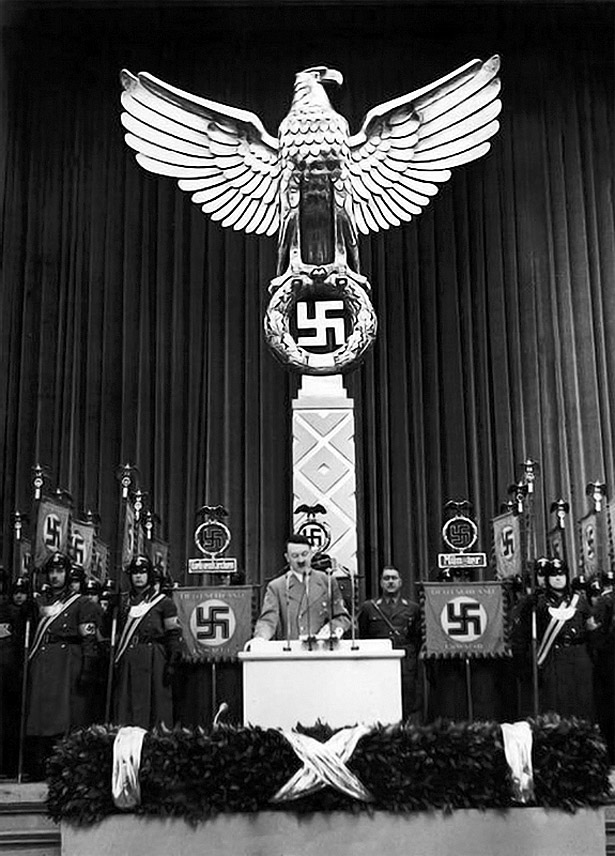

-Adolf Hitler, Berlin, February 17, 1939